On the 29th of December, 1170, Thomas Becket was murdered in Cantabury Cathedral, but I’ve already posted about that. On the same day in 1989 the Czech writer, philosopher and dissident, Václav Havel, was elected the first post-communist President of Czechoslovakia.

Václav Havel (1936–2011) was a playwright, essayist, dissident, and statesman who became one of the most significant figures in the political transformation of Central and Eastern Europe in the late twentieth century. He is remembered not only as the final President of Czechoslovakia, but also as the first President of the Czech Republic and an emblem of the power of conscience in politics.

Havel was born in Prague on the 5th of October, 1936, into a prominent, intellectual, and affluent family. The Havel family’s wealth and status were a burden after the Communist coup of 1948, as the regime discriminated against bourgeois backgrounds. Havel was allowed only limited access to formal education; he could not study humanities at a university because of his background and was instead directed towards technical schooling. Despite these limitations, he gravitated towards the theatre and literature, which became his lifelong passion.

In the 1960s, Havel emerged as a leading figure in the Czechoslovak cultural scene. He began writing plays that reflected the absurdity and dislocation of life under authoritarian rule. His works, such as The Garden Party (1963) and The Memorandum (1965), are often associated with the Theatre of the Absurd, presenting bureaucracy and ideology as surreal forces that distort human behaviour. Havel’s plays were at once humorous and cutting, offering subtle yet potent critiques of the Communist regime.

The Prague Spring of 1968, a period of political reform under Alexander Dubček, was a pivotal moment in Havel’s life. The Warsaw Pact invasion that ended the reforms radicalised his opposition to the regime. In the years following the suppression of the Prague Spring, Havel became increasingly involved in dissident activities, supporting underground cultural life and advocating for human rights. His political essays, notably The Power of the Powerless (1978), articulated the moral and spiritual dimensions of dissent. He argued that individuals living “in truth” could undermine the hollow legitimacy of oppressive regimes, while those who conformed perpetuated the system’s lies.

Havel was a central figure in Charter 77, a civic initiative launched in 1977 that criticised the government for failing to uphold human rights commitments under the Helsinki Accords. He co-founded the movement and became a key spokesperson, despite persistent surveillance, harassment, and imprisonment. His periods of incarceration between 1977 and 1989 strengthened his international reputation as a symbol of peaceful resistance and intellectual courage.

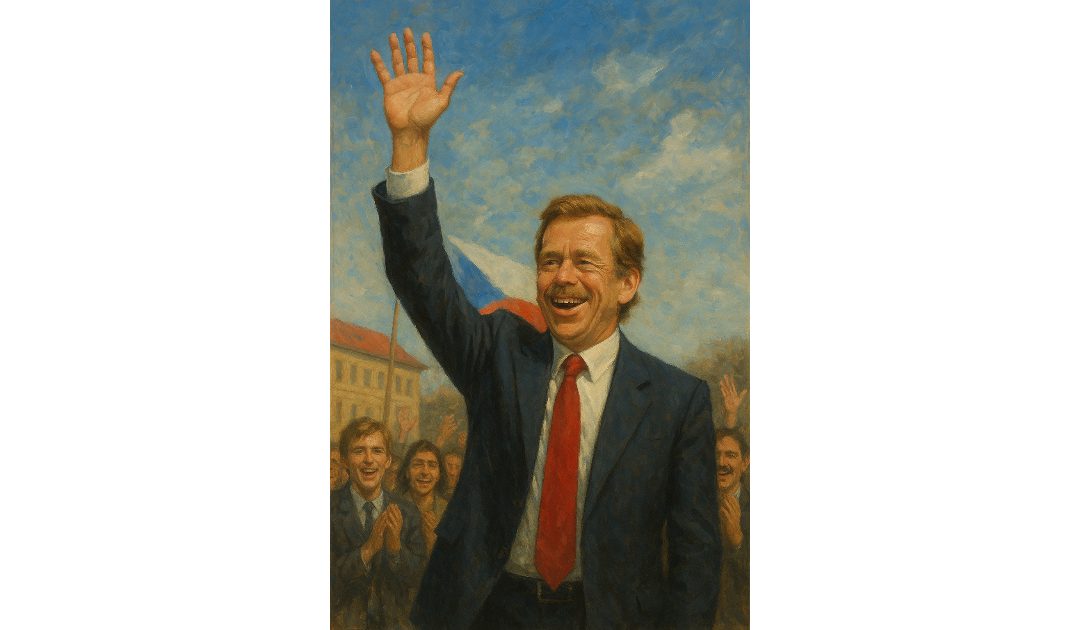

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 transformed Havel from an imprisoned dissident into a national leader. As popular protests swept Czechoslovakia and the Communist regime crumbled, Havel became the voice of the Civic Forum, the broad movement coordinating the transition. Within weeks, he was elected President of Czechoslovakia on 29 December 1989, an extraordinary ascent from political exile to the highest office.

As president, Havel faced the dual challenge of guiding a post-Communist society and addressing the growing tensions between Czechs and Slovaks. He advocated for democratic principles, human rights, and integration with Western Europe, yet he was a reluctant politician by temperament. In 1993, following the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Havel became the first President of the Czech Republic, a position he held until 2003. His presidency was marked by efforts to strengthen civil society, promote NATO and EU membership, and maintain a moral tone in public life, though he often clashed with more pragmatic politicians.

Beyond his political career, Havel remained a writer and public intellectual. His essays and memoirs reflect on the moral responsibilities of leadership and the dangers of cynicism in democratic societies. He received numerous international honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Gandhi Peace Prize, and he was widely admired as a symbol of non-violent change.

Havel died on the 18th of December, 2011, but his legacy endures. He represents the transformative power of authenticity, art, and moral conviction in the face of oppression. His life demonstrates that literature and politics can intersect to shape history, and that the courage of individuals can illuminate the path for entire nations. Today, Václav Havel is remembered not only as a leader but also as a moral compass for the turbulent journey from dictatorship to democracy.

Václav Havel (1936–2011) was a playwright, essayist, dissident, and statesman who became one of the most significant figures in the political transformation of Central and Eastern Europe in the late twentieth century. He is remembered not only as the final President of Czechoslovakia, but also as the first President of the Czech Republic and an emblem of the power of conscience in politics.

Havel was born in Prague on the 5th of October, 1936 into a prominent, intellectual, and affluent family. The Havel family’s wealth and status were a burden after the Communist coup of 1948, as the regime discriminated against bourgeois backgrounds. Havel was allowed only limited access to formal education; he could not study humanities at a university because of his background and was instead directed towards technical schooling. Despite these limitations, he gravitated towards the theatre and literature, which became his lifelong passion.

In the 1960s, Havel emerged as a leading figure in the Czechoslovak cultural scene. He began writing plays that reflected the absurdity and dislocation of life under authoritarian rule. His works, such as The Garden Party (1963) and The Memorandum (1965), are often associated with the Theatre of the Absurd, presenting bureaucracy and ideology as surreal forces that distort human behaviour. Havel’s plays were at once humorous and cutting, offering subtle yet potent critiques of the Communist regime.

The Prague Spring of 1968, a period of political reform under Alexander Dubček, was a pivotal moment in Havel’s life. The Warsaw Pact invasion that ended the reforms radicalised his opposition to the regime. In the years following the suppression of the Prague Spring, Havel became increasingly involved in dissident activities, supporting underground cultural life and advocating for human rights. His political essays, notably The Power of the Powerless (1978), articulated the moral and spiritual dimensions of dissent. He argued that individuals living “in truth” could undermine the hollow legitimacy of oppressive regimes, while those who conformed perpetuated the system’s lies.

Havel was a central figure in Charter 77, a civic initiative launched in 1977 that criticised the government for failing to uphold human rights commitments under the Helsinki Accords. He co-founded the movement and became a key spokesperson, despite persistent surveillance, harassment, and imprisonment. His periods of incarceration between 1977 and 1989 strengthened his international reputation as a symbol of peaceful resistance and intellectual courage.

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 transformed Havel from an imprisoned dissident into a national leader. As popular protests swept Czechoslovakia and the Communist regime crumbled, Havel became the voice of the Civic Forum, the broad movement coordinating the transition. Within weeks, he was elected President of Czechoslovakia on the 29th of December, 1989, an extraordinary ascent from political exile to the highest office.

As president, Havel faced the dual challenge of guiding a post-Communist society and addressing the growing tensions between Czechs and Slovaks. He advocated for democratic principles, human rights, and integration with Western Europe, yet he was a reluctant politician by temperament. In 1993, following the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Havel became the first President of the Czech Republic, a position he held until 2003. His presidency was marked by efforts to strengthen civil society, promote NATO and EU membership, and maintain a moral tone in public life, though he often clashed with more pragmatic politicians.

Beyond his political career, Havel remained a writer and public intellectual. His essays and memoirs reflect on the moral responsibilities of leadership and the dangers of cynicism in democratic societies. He received numerous international honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Gandhi Peace Prize, and he was widely admired as a symbol of non-violent change.

Havel died on the 18th of December, 2011, but his legacy endures. He represents the transformative power of authenticity, art, and moral conviction in the face of oppression. His life demonstrates that literature and politics can intersect to shape history, and that the courage of individuals can illuminate the path for entire nations. Today, Václav Havel is remembered not only as a leader but also as a moral compass for the turbulent journey from dictatorship to democracy.