It was on the 26th of November, 1922, that Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon became the first people in over 3,000 years to enter the tomb of Tutankhamun. In 2013 Claire and I cruised the Nile and visited Thebes and the Valley of the Kings. In 2020 we visited the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery in London.

Tutankhamun, often referred to as the Boy King, is one of the most famous pharaohs of ancient Egypt, largely due to the extraordinary discovery of his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Born around 1341 BC, he ascended to the throne at roughly nine years old during the Eighteenth Dynasty and ruled for approximately a decade. His reign coincided with a turbulent period in Egyptian history, following the religious upheavals initiated by Akhenaten, who had temporarily shifted the kingdom’s focus to worship of the sun disc, Aten. Tutankhamun is believed to have been the son of Akhenaten, though his lineage has long been a subject of scholarly debate. His queen was Ankhesenamun, thought to be his half-sister, and his reign involved restoring traditional religious practices, particularly the worship of the god Amun, and moving the royal court back to Thebes.

Despite his fame today, Tutankhamun was a relatively minor pharaoh in his lifetime. His early death, at around 18 or 19 years of age, cut short any major achievements he might have had. The cause of his death remains uncertain, with theories ranging from a chariot accident to genetic disorders or disease. After his death, Tutankhamun was buried in a comparatively small tomb, which some scholars believe was not originally intended for a pharaoh. This may have contributed to its survival largely intact for over 3,000 years, hidden beneath debris and later constructions in the Valley of the Kings.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, designated KV62, was discovered in 1922 by the British archaeologist Howard Carter, working on an expedition funded by Lord Carnarvon. This discovery is considered one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century. Carter had been excavating in the Valley of the Kings for several seasons without major success. Yet, he remained convinced that Tutankhamun’s tomb had not been found, despite earlier claims that the valley had been thoroughly searched.

On the 4th of November, 1922, Carter’s team uncovered the first step leading down to the tomb’s entrance, hidden beneath workmen’s huts from later periods. After carefully clearing the stairway, they found a sealed doorway bearing the royal necropolis stamp. It would take several weeks of preparation before the team was ready to breach the inner chambers. On the 26th of November, 1922, Carter peered through a small hole into the tomb by candlelight. When asked by Lord Carnarvon if he could see anything, Carter famously replied, “Yes, wonderful things.”

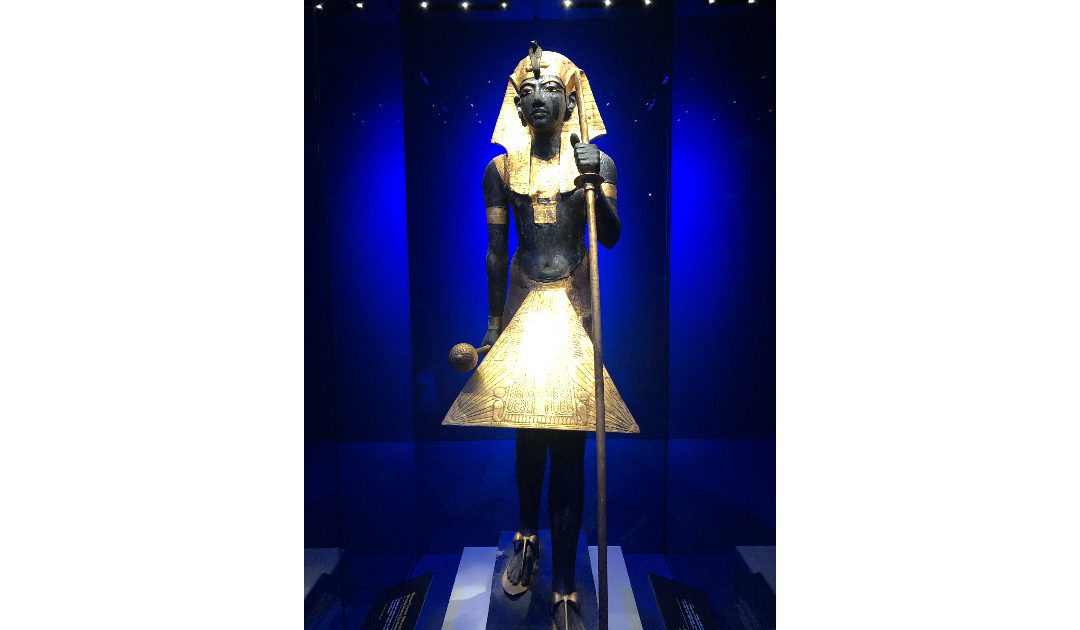

The tomb contained an astonishing array of treasures: gilded furniture, chariots, weapons, clothing, jewellery, and ritual objects. The most iconic find was the nested series of coffins, with the innermost made of solid gold, which contained Tutankhamun’s mummy adorned with the now world-famous gold funerary mask. The scenes within the burial chambers and the careful arrangement of goods offered unparalleled insight into royal life, beliefs about the afterlife, and the craftsmanship of the New Kingdom.

Unlike other royal tombs, which had often been looted in antiquity, Tutankhamun’s tomb was almost fully intact, although evidence suggested that it had been entered twice in ancient times. Its relative secrecy and the haphazard placement of some items indicate that the burial may have been hurried, likely due to the young king’s unexpected death. The tomb’s modest size and unusual layout further support the theory of a sudden interment.

The discovery of the tomb sparked worldwide fascination with ancient Egypt, often referred to as “Tutmania.” Artefacts from the tomb toured internationally, inspiring everything from fashion to cinema. The find also fuelled popular myths, such as the “curse of the pharaohs,” after the sudden death of Lord Carnarvon in 1923. In reality, most of the excavation team lived long lives, but the tale of the curse captured the imagination of the public. The exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery confirmed that Lord Carnarvon had died from an infected mosquito bite, and that the curse myth had been invented by the Daily Mail to sell newspapers.