On the 17th of February, 1801, a tie in the Electoral College between Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson was resolved when Jefferson was elected President of the United States and Burr Vice President.

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was one of the most influential figures in American history: a revolutionary thinker, principal author of the Declaration of Independence, diplomat, political philosopher, and the third president of the United States. His ideas about liberty, republican government, and individual rights helped shape the identity of the new nation, even as contradictions within his own life—most notably his relationship with slavery—continue to provoke debate.

Jefferson was born on the 13th of April, 1743, at Shadwell, a plantation in colonial Virginia, into a prosperous planter family. He received an excellent education, studying Latin, Greek, mathematics, philosophy, and law. At the College of William & Mary he absorbed Enlightenment ideas, particularly those of John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton, whose emphasis on reason and natural rights profoundly influenced his political thinking. Trained as a lawyer, Jefferson entered public life in the Virginia House of Burgesses in the 1760s, where he began to oppose British imperial policies.

His rise to prominence came during the American Revolution. In 1776, at the age of thirty-three, Jefferson was chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence. Drawing on Enlightenment philosophy, the document famously proclaimed that “all men are created equal” and endowed with inalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Though revised by Congress, Jefferson’s eloquence and moral clarity made the Declaration a foundational statement of American ideals and one of the most influential political texts in history.

During the war, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia, a role that proved difficult amid British invasions and internal disorder. Though criticised at the time, his reputation recovered, and in the 1780s he became a key diplomat. As minister to France from 1785 to 1789, Jefferson witnessed the early stages of the French Revolution and sympathised deeply with its republican aspirations. His time in Europe broadened his cultural interests and reinforced his belief in popular sovereignty and resistance to tyranny.

Returning to the United States, Jefferson served as the nation’s first Secretary of State under President George Washington. In this role he became a central figure in the emerging party system, clashing with Alexander Hamilton over the nature of the federal government. Jefferson championed a strict interpretation of the Constitution, states’ rights, and an agrarian republic of independent farmers, while Hamilton favoured a strong central government and commercial economy. These disputes led Jefferson to co-found the Democratic-Republican Party, America’s first organised opposition party.

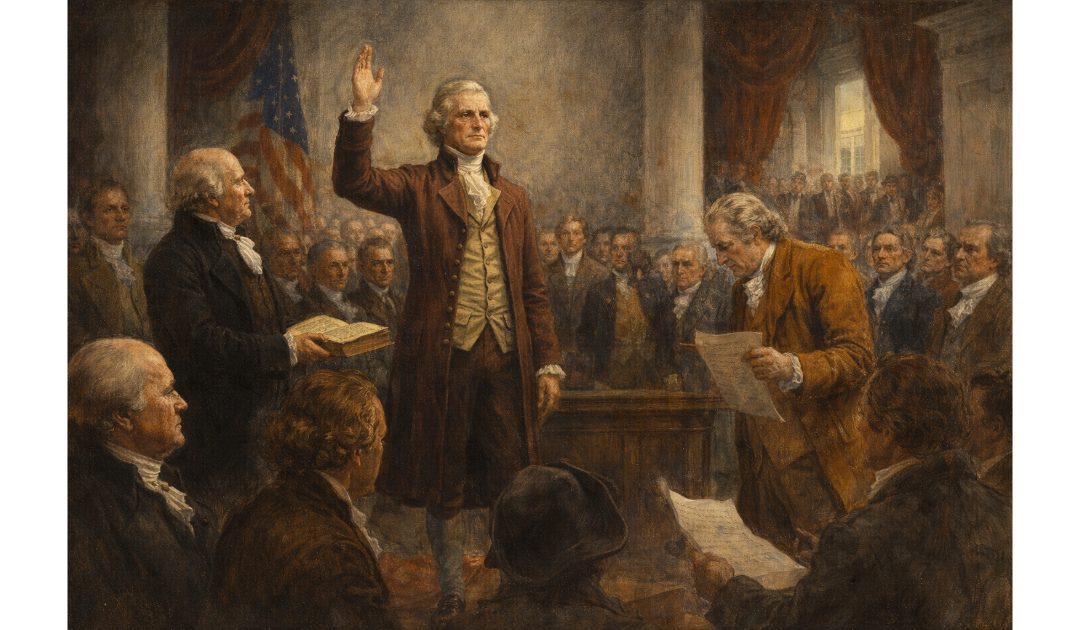

Jefferson became vice president under John Adams in 1797, a strained arrangement marked by deep political rivalry. In the bitter election of 1800, Jefferson defeated Adams, an event he later described as the “Revolution of 1800” because it marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties in modern history.

As president from 1801 to 1809, Jefferson sought to govern with simplicity and restraint. He reduced government spending, cut taxes, and aimed to limit federal power. His greatest achievement was the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which doubled the size of the United States and secured control of the Mississippi River. Though Jefferson worried that the purchase exceeded his constitutional authority, it proved decisive in America’s expansion and future prosperity.

Jefferson’s presidency also faced challenges. His response to British and French interference with American shipping culminated in the Embargo Act of 1807, which banned American trade with foreign nations. Intended to avoid war and protect neutrality, the embargo instead damaged the U.S. economy and proved deeply unpopular, undermining Jefferson’s final years in office.

After retiring from the presidency, Jefferson devoted himself to education and intellectual pursuits. His proudest achievement late in life was the founding of the University of Virginia, which he envisioned as a modern, secular institution dedicated to free inquiry. He designed its buildings, curriculum, and principles, seeing education as essential to the survival of republican government.

Jefferson died on the 4th of July, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of American independence, the same day as John Adams. His legacy is immense but complex. He articulated enduring ideals of freedom and equality, yet owned enslaved people throughout his life. This contradiction lies at the heart of modern debates about Jefferson: a visionary advocate of liberty who lived within—and benefited from—a system that denied it to others. Nonetheless, his influence on American political thought and democratic ideals remains profound and enduring.