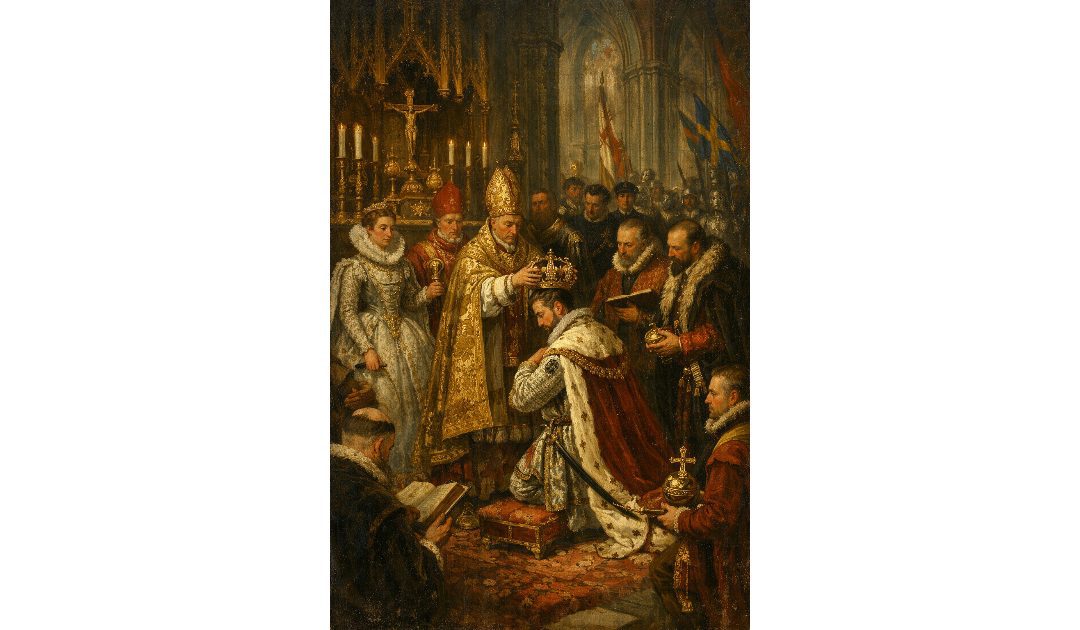

On the 19th of February, 1594, Sigismund III was crowned King of Sweden. Sigismund III of Sweden, also known as Sigismund III Vasa (1566–1632), was one of the most complex and consequential monarchs of early modern Europe. He reigned as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 and as King of Sweden from 1592 until his deposition in 1599. His life and rule sat at the fault line between Catholicism and Protestantism, between hereditary monarchy and noble power, and between the competing ambitions of Northern and Eastern Europe. Few rulers better illustrate how religion, dynasty, and geopolitics intertwined at the end of the sixteenth century.

Sigismund was born in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden, the son of John III of Sweden and Catherine Jagiellon, a Polish Catholic princess. This mixed heritage profoundly shaped his destiny. Sweden, under the Vasa dynasty, had embraced Lutheran Protestantism, while Poland-Lithuania remained one of Europe’s great Catholic powers. Raised largely in Poland after his mother’s death, Sigismund grew into a devout Catholic, educated by Jesuits and imbued with the ideals of the Counter-Reformation. This religious identity would later prove disastrous for his Swedish crown.

In 1587, following the death of King Stephen Báthory, Sigismund was elected King of Poland by the Polish nobility, becoming Sigismund III. Poland-Lithuania was an elective monarchy, and Sigismund ruled under the constraints of powerful nobles (the szlachta) and a parliament (the Sejm). Five years later, in 1592, he inherited the throne of Sweden upon the death of his father, briefly uniting the crowns of Sweden and Poland-Lithuania. On paper, this created one of the largest political entities in Europe, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

In practice, the union was fragile from the outset. Sweden was staunchly Lutheran and deeply suspicious of Sigismund’s Catholicism and his long absences abroad. Although Sigismund promised to uphold Swedish religious laws, many feared he intended to restore Catholicism. Leadership of the opposition fell to his uncle, Duke Charles of Södermanland (later Charles IX), who rallied Protestant clergy and nobles against the king. Tensions escalated into open conflict, culminating in Sigismund’s defeat at the Battle of Stångebro in 1598. In 1599, the Swedish Riksdag formally deposed him. Sigismund never accepted this loss and would spend the rest of his life attempting—unsuccessfully—to reclaim the Swedish crown.

While his Swedish reign was short and unhappy, Sigismund’s rule in Poland-Lithuania lasted over four decades and was far more consequential. His reign coincided with Poland-Lithuania’s final period as a great European power. Sigismund pursued ambitious foreign policies, particularly in the Baltic region, seeking dominance over trade routes and ports. His dynastic conflict with Sweden contributed directly to a series of Polish-Swedish wars, which would drain both states and shape Baltic politics for generations.

Sigismund was also deeply involved in the chaotic affairs of Russia during the Time of Troubles. Polish forces intervened repeatedly, and in 1610 they even occupied Moscow. For a brief moment, Sigismund hoped to place his son, Władysław, on the Russian throne—or even claim it himself. These ambitions ultimately failed, but they marked the furthest eastern reach of Polish influence and left a lasting legacy of hostility between Poland and Russia.

Domestically, Sigismund was a committed supporter of the Counter-Reformation. He patronised the Jesuits, promoted Catholic education, and encouraged the return of churches from Protestant to Catholic hands. Yet Poland-Lithuania remained remarkably religiously diverse during his reign, home to Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Orthodox Christians, Jews, and Muslims. While Sigismund personally favoured Catholicism, he generally worked within the legal framework of religious toleration established earlier in the century, though tensions increased over time.

Culturally, Sigismund III was an important patron of the arts. He moved the Polish royal residence from Kraków to Warsaw, helping transform Warsaw into a permanent political capital. An accomplished painter and goldsmith himself, he encouraged Baroque art and architecture, leaving a visible mark on Polish cultural life.

Sigismund III died in 1632, having never relinquished his claim to the Swedish throne. His legacy is deeply divided. In Sweden, he is often remembered as a foreign, Catholic ruler whose ambitions threatened national independence. In Poland, he is seen as a powerful but controversial monarch: pious, cultured, and ambitious, yet often criticised for prioritising dynastic goals over political compromise. Above all, Sigismund III stands as a ruler whose life embodied the religious and political conflicts of early modern Europe—conflicts that would shape the continent for centuries to come.