The Pilgrimage of Grace began on 13th October 1536, almost immediately after the suppression of the Lincolnshire Rising. One of the primary catalysts for the Pilgrimage of Grace was the religious upheaval brought about by Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church. The Dissolution of the Monasteries, a policy initiated by the king to seize and dissolve Catholic monastic houses, struck at the heart of religious life in England. This move threatened the monastic communities, their lands, and the social welfare they provided to the people. The uprising, fuelled by the desire to preserve Catholicism and its institutions, gathered support from across the social spectrum, including nobles, gentry, and commoners.

Furthermore, the grievances expressed during the Pilgrimage of Grace extended beyond religious concerns and encompassed broader political and economic issues. The poor economic conditions in the countryside, exacerbated by enclosures and the erosion of traditional rights, added fuel to the rebellion. The protestors sought to protect their livelihoods and preserve their rights and privileges against the encroachment of the crown and its agents. The uprising thus became a platform for voicing the frustrations of the common people and challenging the centralisation of power in the hands of the king and his court.

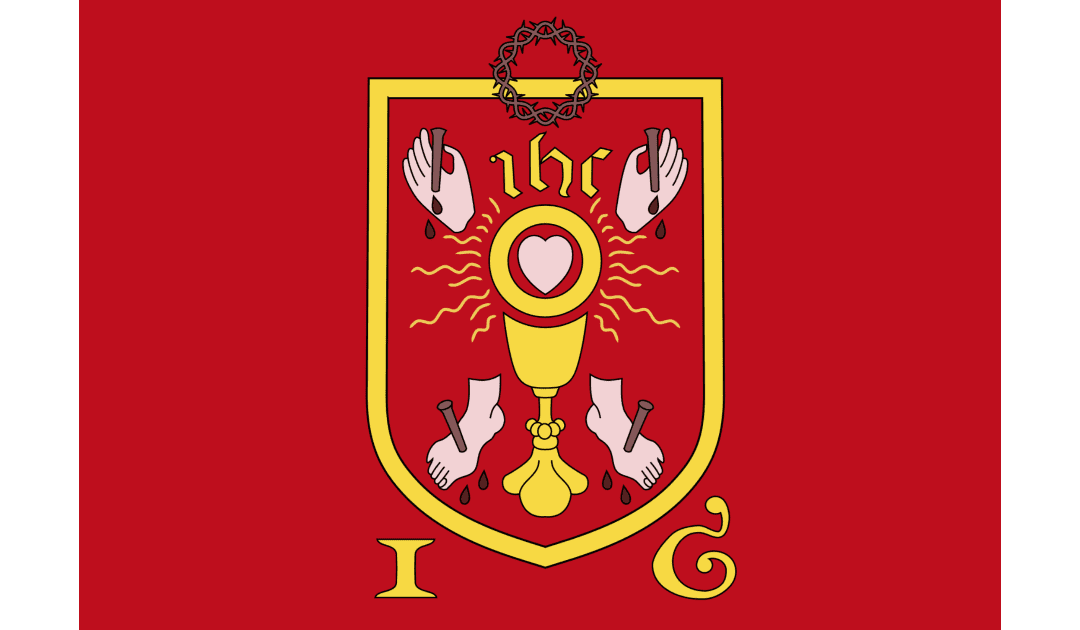

The Pilgrimage of Grace is also notable for its scale and organisation. Robert Aske led a force of tens of thousands of rebels, who marched under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ. This vast and united movement was able to negotiate successfully with the king’s representatives, securing promises of religious freedom and a cessation of the dissolution of monasteries. However, these promises were short-lived, as Henry VIII ultimately reneged on his concessions, leading to a brutal suppression of the uprising and the execution of its leaders.

The Pilgrimage of Grace remains a significant episode in English history, illustrating the resilience of traditional beliefs, the power of collective action, and the limits of royal authority. It served as a warning to Henry VIII and subsequent monarchs that the will of the people could not be ignored. Moreover, the uprising highlighted the complex and multifaceted nature of popular discontent, encompassing religious, economic, and political grievances.

Henry VIII was succeeded by Edward VI who wanted everyone in England to be Protestant, and introduced the Book of Common Prayer. He died when he was just 15, and was succeeded, after the nine day reign of Lady Jane Grey, by his eldest sister, Mary I. She insisted everyone should be Catholic and became known as Bloody Mary for her burning of heretic Protestants. She was succeeded by Elizabeth I, a Protestant. My 11th great-uncle, Sir Anthony Standen grew up in these tumultuous times. He was a Catholic who was Walsingham’s key spy supplying intelligence which helped defeat the Spanish Armada of Mary I’s husband, King Phillip II. The first book of my Sir Anthony Standen Adventures tells his story.