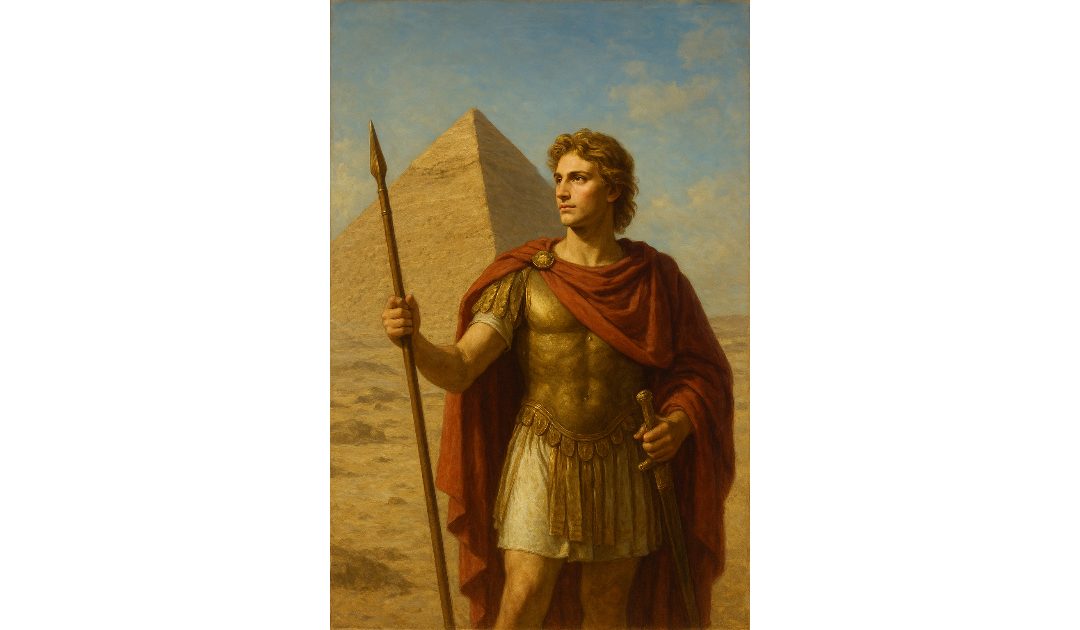

On the 14th of November, 332 BCE, Alexander the Great was crowned pharaoh of Egypt, but I recently wrote about him. Also on 14th of November Moby Dick was published in the USA in 1851, but I have also written about that. So I have decided to write about the pharaohs of Egypt, since Claire and I thoroughly enjoyed our Nile cruise in 2012, and visit to the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery in 2013.

The pharaohs of ancient Egypt were the rulers of one of the most remarkable civilisations in human history, governing a land that stretched along the fertile banks of the Nile for over three millennia. Revered as both political leaders and divine figures, the pharaohs embodied authority, religious power, and the centralised state that maintained Egypt’s stability and grandeur. Their legacy is etched into the monumental architecture, vast burial sites, and rich cultural heritage that continues to fascinate the world today.

The word “pharaoh” itself is derived from the Egyptian term per-aa, meaning “great house”, originally referring to the royal palace rather than the individual ruler. Over time, it came to symbolise the king himself, who was considered the earthly embodiment of the gods. Pharaohs were believed to be chosen by the gods, acting as intermediaries between the divine and mortal worlds. This divine kingship was central to Egyptian ideology, ensuring that the ruler’s commands carried spiritual as well as temporal weight.

Egyptian history is often divided into three major periods – the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom – with intervening Intermediate Periods marked by political fragmentation or foreign rule. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE) presided over a flourishing state and are best remembered for their ambitious pyramid-building projects. The most famous of these rulers include Djoser, who commissioned the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, and Khufu, responsible for the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. These monumental tombs reflected the belief in an eternal afterlife and the pharaoh’s desire to secure his divine status for eternity.

The Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) saw a renaissance in art, literature, and administration. Pharaohs like Mentuhotep II and Senusret III emphasised both military strength and benevolent governance, portraying themselves as shepherds of their people. During this time, Egyptian influence extended into Nubia, and complex irrigation systems supported agricultural growth. Yet the stability of the Middle Kingdom eventually gave way to the Second Intermediate Period, during which Egypt experienced foreign incursions, most notably by the Hyksos, a Semitic people who introduced new military technologies such as the horse-drawn chariot.

The New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE) represented the height of Egyptian power and prestige. Pharaohs like Ahmose I expelled the Hyksos and laid the foundations for a period of territorial expansion and wealth. The empire stretched into the Levant and deep into Nubia, bringing in tribute and resources that funded grand temples and monumental statues. Among the most celebrated pharaohs of this era were Hatshepsut, one of the few female rulers, who oversaw a period of peace and vast trade expeditions; Thutmose III, a brilliant military strategist; and Amenhotep III, under whom Egyptian art and architecture reached new heights.

The 18th Dynasty also produced Akhenaten, a pharaoh known for his radical religious reforms. He attempted to replace the traditional pantheon with the worship of a single sun deity, Aten, shifting the artistic and cultural fabric of Egypt. His reign is often linked with the famous Nefertiti, his queen, and their son, Tutankhamun, whose nearly intact tomb would capture global attention in 1922. Although Tutankhamun’s reign was relatively short and politically unremarkable, the wealth of treasures buried with him provided an unparalleled window into the splendour of pharaonic life.

Ramesses II, often called Ramesses the Great, epitomised the might of the New Kingdom. His reign of over six decades (1279–1213 BCE) was marked by monumental building projects, including the temples at Abu Simbel, and celebrated military campaigns, including the famous Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites. His self-promotion ensured that his image dominated temples and inscriptions across the land, cementing his legacy as one of Egypt’s most iconic rulers.

Despite their power, the pharaohs faced persistent challenges. Maintaining control over a vast territory required a complex bureaucracy, loyal local governors, and continuous military vigilance. Natural disasters, such as low Nile floods, could provoke famine and unrest, undermining the pharaoh’s divine image. In the later periods, Egypt suffered invasions by foreign powers, including the Assyrians, Persians, and eventually the Greeks under Alexander the Great, ending the era of native pharaohs.

The pharaohs of Egypt left a profound impact on world history. They were at once earthly monarchs and divine symbols, guardians of a civilisation that contributed to art, architecture, writing, and religious thought. The pyramids, temples, and tombs they built remain enduring testaments to their ambition and vision. Even today, the lives and deeds of these extraordinary rulers capture the imagination, offering insight into the extraordinary achievements and enduring mysteries of ancient Egypt.