On the 27th of October, 1553, Michael Servetus was burnt alive on a pyre of his own books. He features in Called to Account, the fourth book in the Sir Anthony Standen Adventures. A key character, Manuel, is a doctor of medicine. The main theme of the book is racism and blood is a related theme. Manuel is a proponent of Michael Serverus’s writings on the pulmonary circulation.

Michael Servetus (1511–1553) was a pioneering thinker of the Renaissance, whose contributions to theology, medicine, and science left an indelible mark on history. Born in Villanueva de Sigena, Aragon (modern-day Spain), he was a polymath fluent in several languages, including Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Servetus’s intellectual pursuits spanned law, theology, geography, and medicine, making him a quintessential Renaissance figure.

Servetus grew up in a Spain steeped in religious fervour and scholastic tradition. His early education remains somewhat obscure, but he probably studied under the guidance of clerics or scholars influenced by humanist ideals. He attended the University of Zaragoza and later studied law at the University of Toulouse in France. It was here that he developed an interest in theology and became critical of orthodox Christian doctrines, particularly the concept of the Trinity.

Servetus’s most controversial work, De Trinitatis Erroribus (“On the Errors of the Trinity”), published in 1531, vehemently criticised the Nicene Creed’s doctrine of the Trinity. He argued for the unity of God, rejecting the traditional belief in God as three distinct persons. This radical stance alienated him from both Catholic and Protestant authorities. Nonetheless, his arguments were part of broader theological debates during the Reformation.

Servetus’s theological ideas were not limited to the Trinity. He also wrote Christianismi Restitutio (“The Restoration of Christianity”) in 1553, where he challenged predestination, a central tenet of Calvinist theology. He emphasised free will, the importance of personal faith, and a direct relationship with God. This work integrated his theological views with his groundbreaking discoveries in medicine.

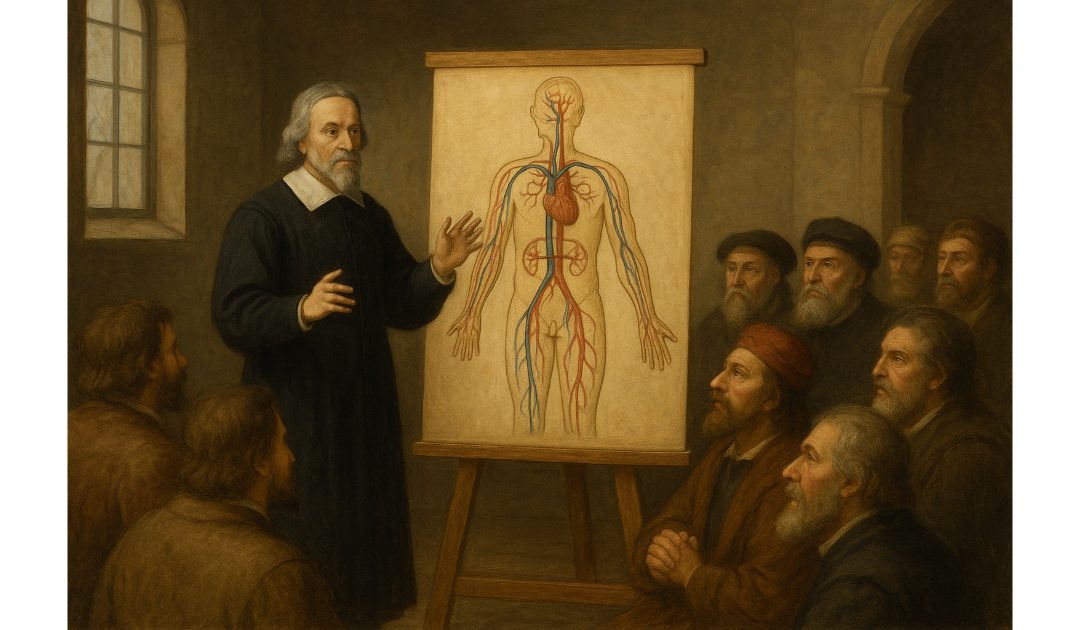

Although theology dominated his life, Servetus made significant contributions to medicine. He studied medicine at the University of Paris, one of the leading medical schools of the time, and became an accomplished physician. His most notable scientific achievement was his description of the pulmonary circulation of blood.

In Christianismi Restitutio, Servetus described how blood travels from the right ventricle of the heart to the lungs, where it is oxygenated, and then flows to the left ventricle. This contradicted the prevailing Galenic theory, which posited that blood passed directly from the right to the left side of the heart through invisible pores. Although his discovery did not gain immediate recognition, it laid the groundwork for later scientists, such as William Harvey, who expanded on the understanding of the circulatory system.

Servetus’s theological views brought him into direct conflict with John Calvin, the influential Protestant reformer in Geneva. The two exchanged heated correspondence, debating issues of predestination and the nature of God. Servetus’s criticisms of Calvin’s doctrines, particularly in Christianismi Restitutio, enraged Calvin.

In 1553, Servetus was arrested in Vienne, France, by Catholic authorities, charged with heresy, and sentenced to death. Remarkably, he escaped prison but made the fateful decision to travel through Geneva, where Calvin held significant influence. Recognised and arrested, Servetus was tried for heresy by the Protestant authorities. Despite opportunities to recant, he remained steadfast in his beliefs.

Servetus’s death sparked widespread debate about religious tolerance and freedom of conscience. Some contemporaries, including Sebastian Castellio, condemned the execution, arguing that it was morally wrong to kill someone for their beliefs. Castellio famously stated, “To kill a man is not to defend a doctrine, but to kill a man.”