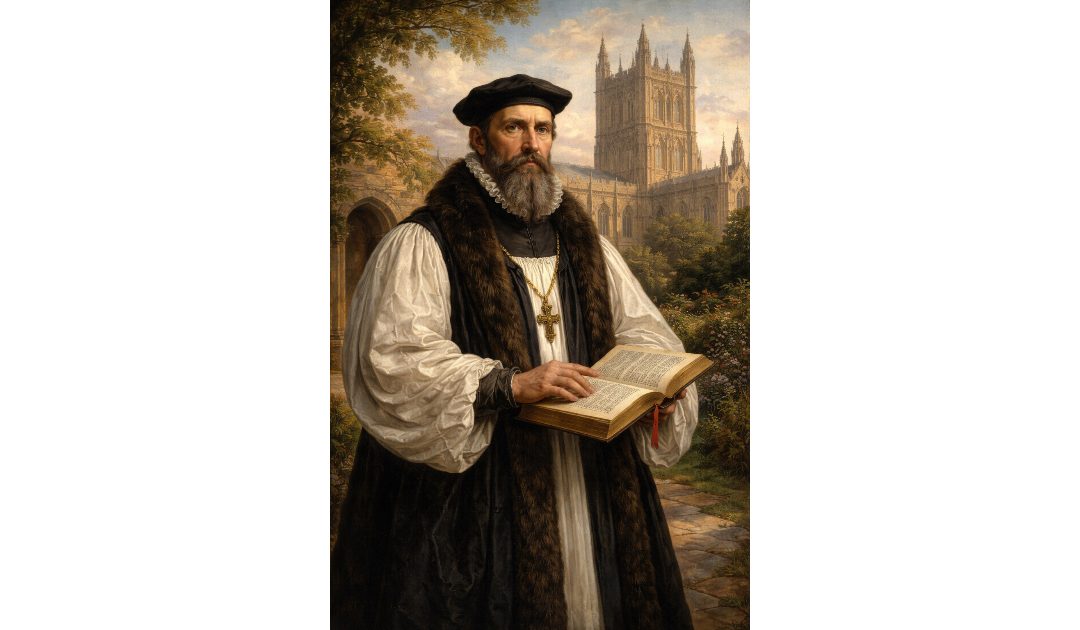

On the 9th of February, 1555, John Hooper the Bishop of Gloucester was burnt at the stake. John Hooper (c.1495–1555), Bishop of Gloucester and later Worcester, was among the most resolute and uncompromising figures of the English Reformation. A theologian shaped by continental Protestantism and a man of austere personal discipline, Hooper’s career was defined by conflict: with ecclesiastical tradition, with fellow reformers, and most notably with conservative churchmen such as Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester. His life, ending in martyrdom under Mary I, made him a lasting emblem of Protestant conscience and resistance.

Born in Somerset around 1495, Hooper was educated at Oxford, where he encountered early evangelical ideas. During the later years of Henry VIII’s reign, his Protestant convictions became increasingly dangerous. Although Henry had broken with Rome, doctrinal reform remained limited, and outspoken evangelicals were vulnerable. Hooper eventually fled England, spending time in Strasbourg and Zürich. There he came under the influence of leading Reformed theologians, absorbing a theology that stressed the absolute authority of Scripture, the rejection of ceremonies lacking biblical warrant, and the moral reformation of church and society.

Hooper returned to England after the accession of Edward VI in 1547, when the balance of power shifted decisively toward Protestant reform. He quickly established himself as a powerful preacher and theological voice. However, his radicalism set him apart even from fellow reformers. This became evident in his conflict with Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, one of the most formidable defenders of traditional Catholic doctrine within the English episcopate. Gardiner, though outwardly compliant with royal supremacy, opposed Protestant theology and resisted changes to doctrine and worship.

Hooper and Gardiner clashed sharply over the direction of the English Church. Hooper publicly criticised Gardiner’s conservatism, accusing him of obstructing true reform and clinging to unscriptural traditions. Gardiner, in turn, regarded Hooper as dangerously extreme, socially disruptive, and theologically subversive. Their rivalry reflected the deeper ideological struggle within Edwardian England: whether reform should proceed cautiously under royal and episcopal authority, or whether it should be driven relentlessly by Scripture regardless of political consequences. Gardiner’s eventual imprisonment during Edward’s reign removed a major obstacle to reformers like Hooper, but their antagonism was well remembered.

Hooper’s uncompromising principles soon brought him into trouble from another direction. In 1550–51 he became embroiled in the “vestments controversy,” refusing to wear the traditional episcopal garments required for his consecration as Bishop of Gloucester. He argued that such vestments were remnants of Roman Catholic superstition and lacked biblical authority. Even Archbishop Thomas Cranmer urged moderation, fearing that Hooper’s defiance undermined order. After imprisonment and prolonged debate, Hooper reluctantly accepted a compromise and was consecrated in 1551.

As Bishop of Gloucester, and later also Bishop of Worcester, Hooper proved a tireless reformer. He emphasised preaching, disciplined negligent clergy, and worked to eradicate what he regarded as residual Catholic practices. His vision of reform was deeply moral: he insisted that true religion must be evident in behaviour, not merely doctrine. His writings and sermons attacked clerical ignorance, corruption, and complacency, and called for a godly commonwealth shaped by Scripture.

The accession of Mary I in 1553 reversed Hooper’s fortunes completely. Mary restored Roman Catholicism and released conservative bishops, including Stephen Gardiner, who now returned to power as Lord Chancellor. Gardiner played a central role in the Marian persecutions, and Hooper became one of his most prominent victims. Their earlier conflict now took on deadly significance. Gardiner presided over examinations and legal proceedings against Protestant leaders, and Hooper was arrested, deprived of his bishoprics, and imprisoned.

During his imprisonment, Hooper was repeatedly examined and pressed to recant. Gardiner and other authorities sought to portray him as obstinate and seditious, but Hooper remained steadfast. He rejected papal authority and Catholic sacramental theology, maintaining that to recant would be to betray God’s truth. His refusal sealed his fate.

In February 1555, Hooper was condemned as a heretic and burned at the stake in Gloucester. The execution was notoriously prolonged due to poorly prepared fuel, subjecting him to extreme suffering. Yet contemporary accounts describe his remarkable composure and faith, as he prayed and encouraged onlookers until death overtook him.

Hooper’s martyrdom was immortalised in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, where he appeared as a model of godly endurance. His earlier conflict with Stephen Gardiner came to symbolise the wider struggle between reformist conscience and authoritarian tradition. Though controversial in life, Hooper’s legacy shaped later Puritan ideals and secured his place as one of the most principled and courageous figures of the English Reformation.