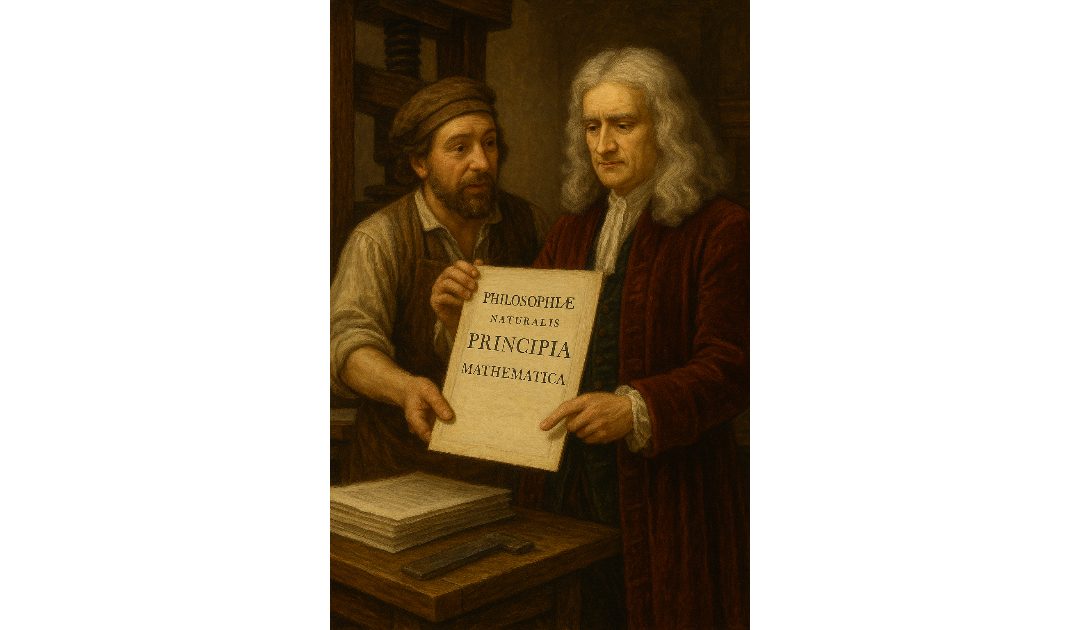

On the 5th of July, 1687, Isaac Newton published Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, often referred to simply as the Principia. It is one of the most influential works in the history of science. It laid the foundations for classical mechanics and transformed the way people understood the natural world. Newton, already a brilliant mathematician and physicist by the 1680s, wrote the Principia to formally express his discoveries about motion, gravity, and the laws that govern physical bodies.

Born in 1643 in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, Newton studied at Cambridge University, where his early work in mathematics and optics began to gain attention. However, it was his formulation of the laws of motion and universal gravitation that would secure his place in scientific history. These ideas crystallized during the 1660s, a period of intense personal study while Cambridge was closed due to plague. Yet it was not until the mid-1680s, when Edmond Halley encouraged and financially supported him, that Newton wrote and published the Principia.

The Principia is written in Latin and structured in three books. In Book I, Newton presents his famous three laws of motion, which describe how forces affect the motion of objects. These principles—an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by an external force; force equals mass times acceleration; and for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction—became cornerstones of physics.

Book II deals with the motion of fluids and resistance. It explores the effects of air and water on objects in motion and critiques the Cartesian vortex theory, which had previously dominated scientific thought. Newton’s rigorous mathematical analysis showed that the mechanical universe could be explained without appealing to mysterious aether or swirling vortices.

Book III, the most revolutionary section, applies Newton’s laws to celestial bodies. Here, he formulates the law of universal gravitation: every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. With this law, Newton explained the elliptical orbits of the planets, the motion of comets, the tides, and even the shape of the Earth.

The Principia did more than provide mathematical models—it changed the intellectual landscape. Newton demonstrated that the universe was orderly and governed by laws that could be discovered and described through reason and mathematics. This mechanistic worldview underpinned the Enlightenment and inspired generations of scientists, from Laplace to Einstein.

Despite its immense difficulty—Newton deliberately used geometric proofs to make it less accessible to casual readers—the Principia was recognized as a masterpiece. Halley’s support in publishing it was crucial, as Newton was reluctant and had disputes with rivals like Robert Hooke.

Isaac Newton’s Principia unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics under one theory, marking the birth of modern physics. Its impact extended beyond science, shaping philosophy, theology, and the Enlightenment’s confidence in reason. It remains one of the greatest scientific works ever written.