I mentioned in my post Practice Makes Progress that I will be on a panel at the Dartmouth Book Festival. I will be on the historical fiction panel with Tim Pears, an award winning writer, who has had an amazingly diverse career. I’m one chapter into his book The Horseman, book one of his West Country Trilogy. He certainly creates some vivid images.

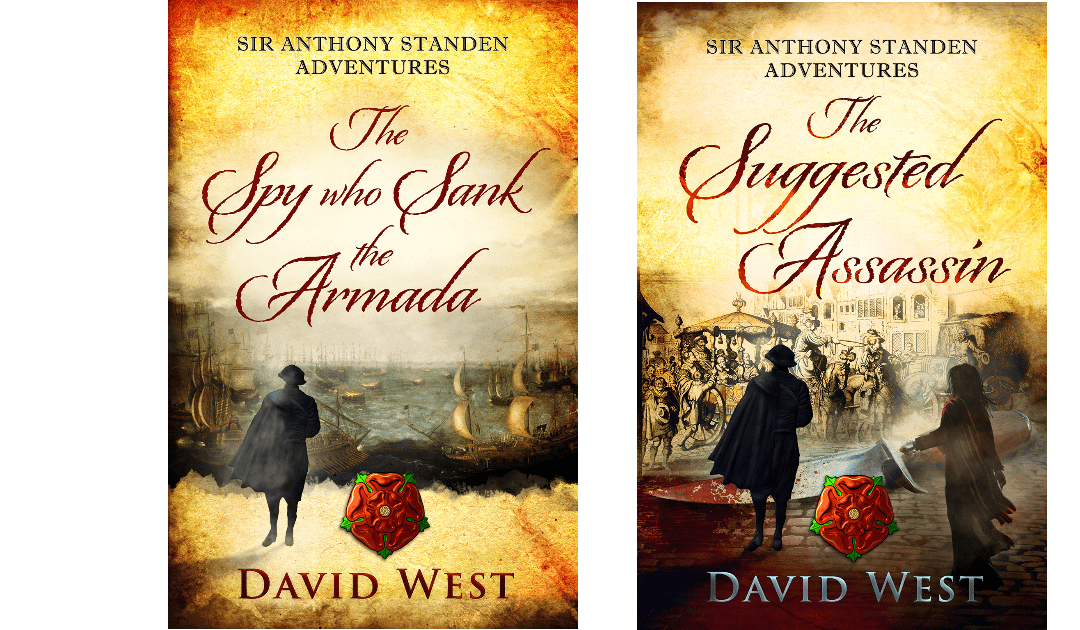

Writing historical fiction was something of an accident for me. If I hadn’t read George Malcolm Thomson’s biography of Sir Francis Drake, I wouldn’t have discovered that my 10th great-grandfather’s elder brother, Sir Anthony Standen, was an Elizabethan spy, providing Francis Walsingham with detailed intelligence on the Spanish Armada. I might have been a contemporary crime writer instead.

I read an article by Hilary Mantel in the Guardian about why she became a historical novelist. Mantel says this: “We carry the genes and the culture of our ancestors, and what we think about them shapes what we think of ourselves, and how we make sense of our time and place. Are these good times, bad times, interesting times? We rely on history to tell us.” I carry some part of Sir Anthony’s DNA, so when writing I always think about what I would do if it were me, grappling with his challenges.

When merging fiction with history we always run the risk of distorting or adapting some aspect of perceived history. However Mantel quotes Patrick Collinson who wrote: “It is possible for competent historians to come to radically different conclusions on the basis of the same evidence. Because, of course, 99% of the evidence, above all, unrecorded speech, is not available to us.”

I love dialogue, and historical fiction affords such scope for imagining all that unrecorded speech. Sometimes in my study I feel like Doctor Who stepping out of the Tardis into 16th century Paris, or Constantinople, or wherever Sir Anthony’s adventures have taken him.