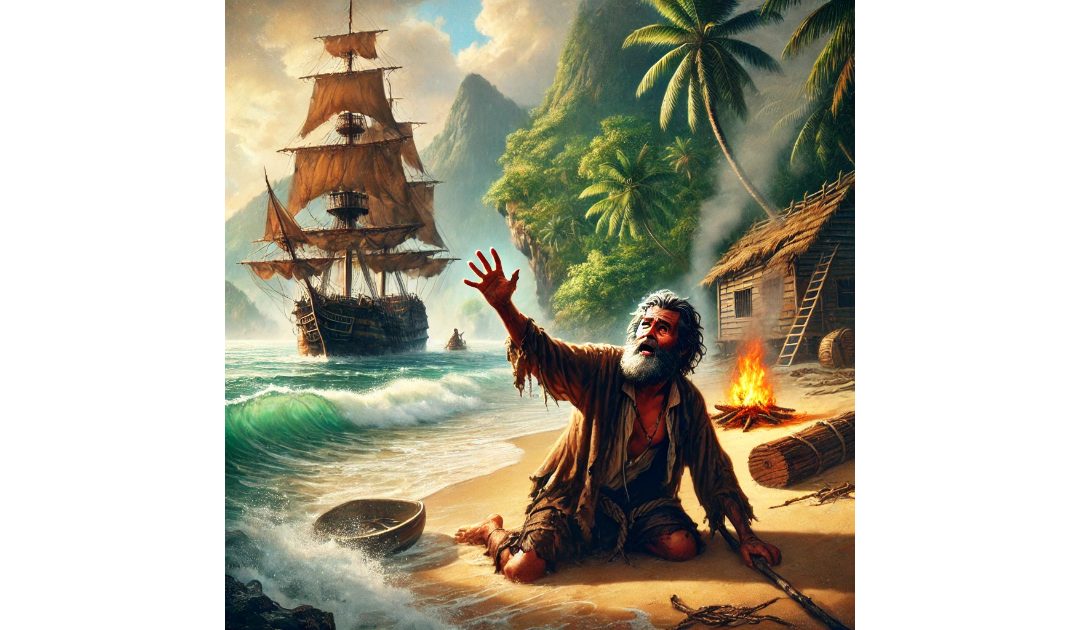

On 19th December 1686 Robinson Crusoe left his desert island after 28 years of being marooned, according to Daniel Defoe’s famous novel.

Daniel Defoe (c. 1660 – April 24, 1731) was an English writer, journalist, businessman, and covert government agent, widely regarded as one of the founders of the modern English novel. Born in London to James Foe, a Nonconformist tallow chandler, Defoe adopted the more genteel surname “Defoe” later in life. His Nonconformist upbringing influenced his political and religious outlook, shaping his later works and career choices.

Defoe initially pursued a business career, engaging in ventures like hosiery and brick-making. Despite early success, his financial fortunes faltered, and he declared himself bankrupt several times. His struggles with debt would later inform his vivid portrayals of economic and social hardship.

Daniel Defoe’s political writings brought him to prominence—and peril. His satirical pamphlet The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702), mocking calls for the harsh persecution of religious dissenters, resulted in his arrest for sedition and a humiliating stint in the pillory. This period marked a turning point in his life. After his release, Daniel Defoe entered the service of the English government as a spy and propagandist under the Tory administration of Robert Harley.

As a secret agent, Defoe was tasked with infiltrating political and religious groups, reporting on dissent, and shaping public opinion through his writings. His most significant espionage work involved Scotland during the politically turbulent period leading to the 1707 Act of Union. Posing as a supporter of Scottish independence, Defoe gathered intelligence and penned persuasive articles to promote unification, helping to ease tensions and sway public sentiment toward the Union.

Daniel Defoe’s literary fame came later in life. At 59, he published Robinson Crusoe (1719), inspired by the real-life castaway Alexander Selkirk. The novel’s themes of survival and self-reliance resonated widely, cementing Defoe’s place in literary history. He followed it with works like Moll Flanders (1722), a gritty exploration of crime and redemption, and A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), a harrowing fictionalized account of the 1665 plague.

Despite his success, Defoe faced ongoing financial struggles and died in 1731, probably from a stroke. He was buried in Bunhill Fields, London.

Today Daniel Defoe is remembered not only as a pioneer of the English novel, but also as a skilled political operative whose espionage shaped the history of his time, reflecting his sharp intellect and adaptability in turbulent times.