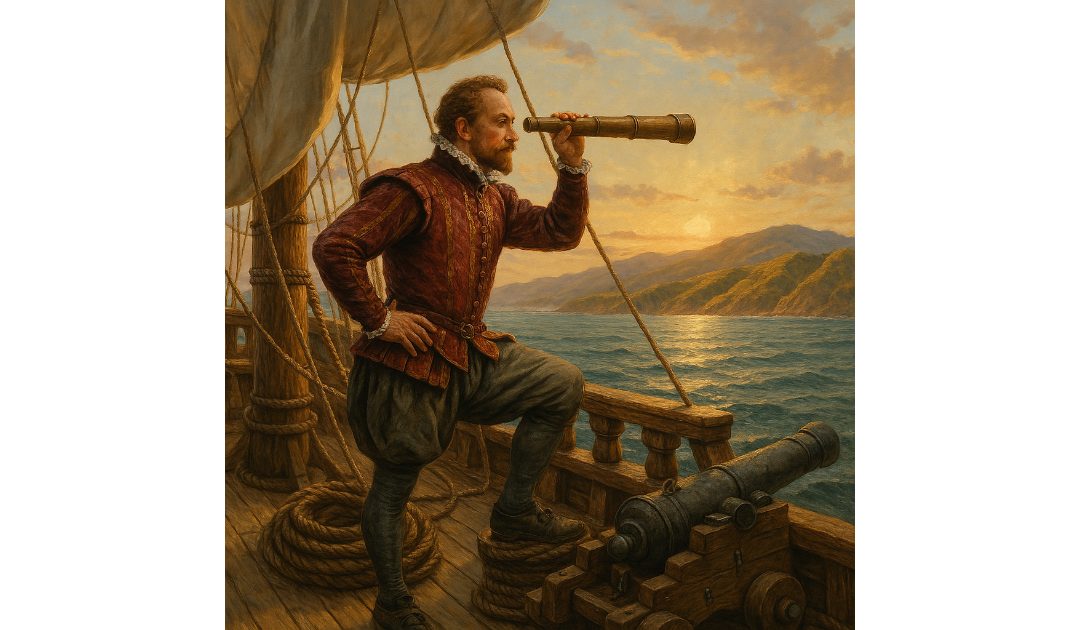

On the 17th of June, 1579, Sir Francis Drake claimed a land which he called “Nova Albion” for England. We now know it as California. I owe a great debt to Drake, since it was in reading the biography of him by George Malcolm Thomson that I discovered the exploits of Sir Anthony Standen, and his espionage role in defeating the Armada. However Drake wasn’t the first European to set foot in California.

The story of California’s discovery begins with Spanish exploration. In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag, became the first European to set foot on what is now California. Cabrillo’s expedition aimed to map the Pacific coast and search for new trading opportunities. He landed at San Diego Bay, marking the start of European interest in the region.

Despite Cabrillo’s initial discovery, significant exploration did not occur until later in the 18th century. By the 1760s, Spain, concerned about Russian advances along the coast, initiated a series of expeditions. Gaspar de Portolá and Father Junípero Serra led these expeditions, establishing a chain of missions from San Diego to Sonoma, which played a crucial role in spreading Spanish influence and Christianity.

The mission system, established between 1769 and 1833, was pivotal in shaping early Californian society. The main objective was to convert Native Americans to Christianity and integrate them into European customs and lifestyles. As a result, 21 missions were founded, serving as religious, agricultural, and administrative centres.

However, the mission system also had profound impacts on indigenous populations. Native people were often subjected to forced labour and European diseases, leading to a dramatic decline in their numbers.

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, and California became a Mexican province. The Mexican government sought to reduce the power of the missions, secularising them in the 1830s. This action led to the redistribution of mission lands, giving rise to the rancho system.

The ranchos marked a period of Mexican influence, with large land grants awarded to individuals, fostering a cattle-based economy. This era also saw diverse cultures begin to intermingle, as Californios, Native Americans, and a growing number of settlers from the United States and Europe began to shape the region’s demographics.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 triggered the California Gold Rush, arguably the most transformative event in the state’s history. Prospectors, known as “forty-niners,” flocked to California in search of wealth, swelling the population and catalysing rapid development. The impact of the Gold Rush was immense: towns and cities sprang up overnight, infrastructure was hastily constructed, and a booming economy took root. By 1850, just two years after the gold discovery, California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state.

In the decades following statehood, California’s economy diversified beyond gold mining. The advent of the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s linked California with the rest of the United States, facilitating trade and migration. Agriculture flourished, particularly with the growth of the citrus industry, while cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles began to develop into urban centres.

By the early 20th century, oil production and Hollywood’s emergence as a film industry powerhouse further solidified California’s economic status. The allure of California as a land of opportunity attracted waves of migrants, enriching its cultural tapestry.

Today, California is synonymous with innovation and diversity. It is home to Silicon Valley, a global technology hub, and boasts a robust economy driven by industries like entertainment, agriculture, and technology. Despite facing challenges such as environmental concerns and housing shortages, California remains a beacon of progress and opportunity. Its history of discovery and development continues to inform its identity as a place where dreams are pursued and realised.