Following yesterday’s post about the Battle of Formigny, we look almost three millennia back to the Battle of Megiddo, which was fought on the 16th of April, 1457 BCE, according to The Middle Chronicle, although some sources disagree.

The Battle of Megiddo is one of the earliest recorded battles in history. It took place in ancient Canaan, where the modern-day city of Megiddo is located, now in northern Israel. This battle is not only significant for its historical implications but also for its detailed documentation by the Egyptians, particularly in the annals of Pharaoh Thutmose III.

Thutmose III, often dubbed the “Napoleon of Egypt,” was a formidable warrior king of the Eighteenth Dynasty. He ascended to power after the death of his stepmother, Hatshepsut, who had acted as regent for the young Pharaoh. Upon assuming full control, Thutmose sought to expand and solidify Egypt’s influence over the Levant region, which was marked by a series of rebellious city-states that posed a threat to Egyptian interests.

During this period, the region was rife with tension. The city-state of Kadesh, located in the Orontes River valley, led a large coalition of Canaanite chieftains against Egyptian hegemony. The rebellion coalesced around the strategically vital city of Megiddo, which served as a crucial juncture for trade routes and military campaigns.

Thutmose III’s campaign began in the spring, his forces traversing northwards along the coastal route known as the “Way of Horus.” Upon reaching the vicinity of Mount Carmel, Thutmose faced a strategic dilemma: to proceed via a circuitous and safer route or to take the direct but perilous path through the Aruna Pass, an action that would expose his army to potential ambush.

In a bold and calculated risk, Thutmose chose the direct route. His decision was based on intelligence and the element of surprise. Leading his troops through the narrow pass, the Pharaoh managed to emerge unscathed on the plains of Megiddo, catching the Canaanite forces off guard.

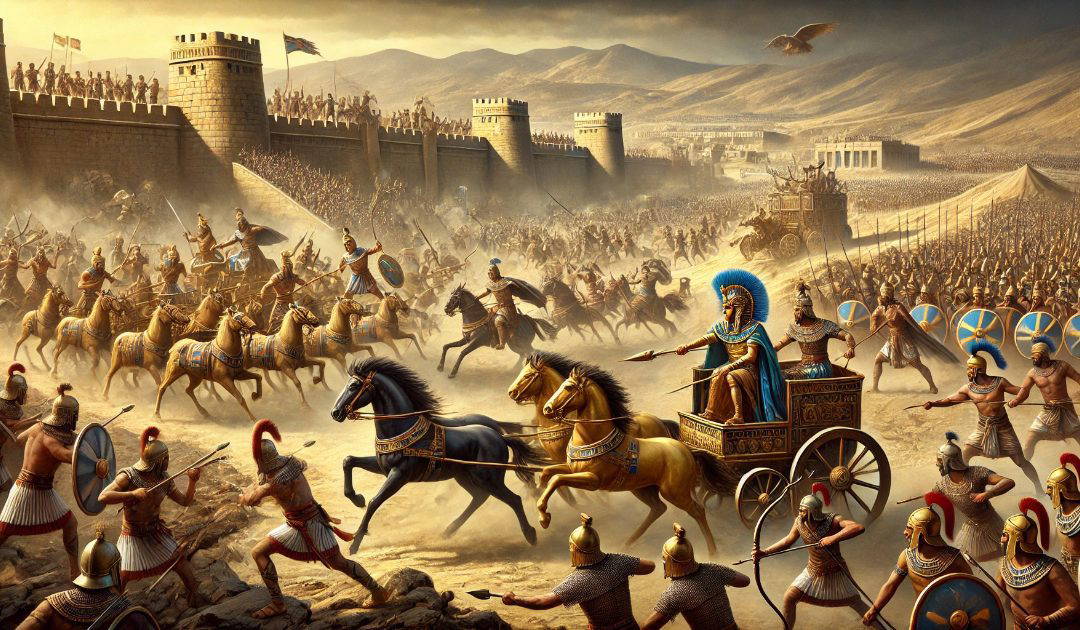

The confrontation at Megiddo unfolded with Egyptian forces arrayed against the coalition of Canaanite armies. Thutmose deployed his army in strategic formations, utilising chariots and infantry in a coordinated assault. The Egyptian chariots, known for their speed and maneuverability, played a pivotal role in breaking through enemy lines.

The Canaanite forces, though formidable in their own right, were not as cohesively organised. The surprise element and strategic acumen of Thutmose III disrupted their defensive preparations, leading to disarray among the coalition ranks.

As the battle intensified, the Canaanite forces eventually retreated into the fortified city of Megiddo. The Egyptians, however, chose not to pursue immediately. Instead, Thutmose ordered a complete siege of the city, cutting off supplies and reinforcements. This tactical decision illustrated Thutmose’s understanding of warfare beyond mere battlefield engagements.

The siege of Megiddo lasted several months. Ultimately, the city capitulated, and the leaders of the rebellion were captured. The victory at Megiddo solidified Egyptian dominance over Canaan, extending Thutmose’s influence far beyond the immediate region.

Thutmose III’s victory at Megiddo is commemorated in the annals of the Temple of Amun in Karnak, where detailed accounts of the campaign were inscribed. These inscriptions provide valuable insights into the logistics, tactics, and strategies employed by ancient Egyptian military forces.

The Battle of Megiddo is a testament to the military prowess and strategic genius of Thutmose III. It not only demonstrates the complex nature of warfare in the ancient world but also underscores the significance of Megiddo as a focal point for historical conflicts. Later, the site of Megiddo would continue to bear witness to numerous battles, becoming synonymous with epic confrontations throughout history.