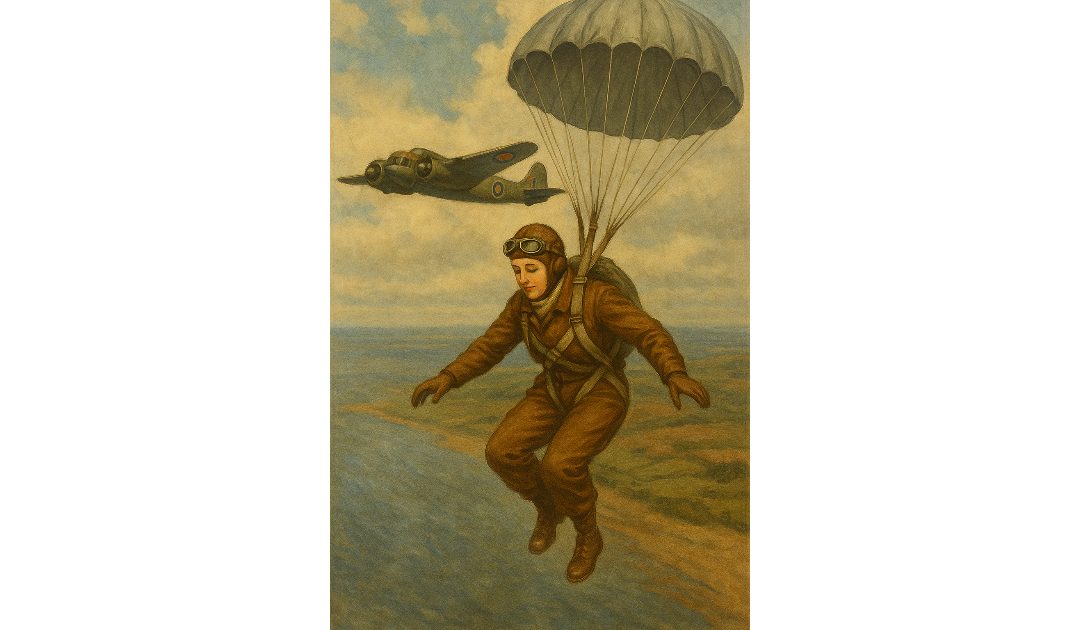

I have posted about my interest in aviation. On the 5th of January, 1941, Amy Johnson disappeared after bailing out of her aeroplane over the River Thames and was presumed dead.

Amy Johnson, born on the 1st of July, 1903, in Kingston upon Hull, was one of Britain’s most celebrated pioneering aviators. Her passion for flight developed during an era when aviation was still in its infancy, and women faced considerable barriers in the field. Johnson’s achievements not only marked significant milestones in aviation history but also symbolised courage, determination, and a challenge to societal expectations of women in the early 20th century.

Johnson studied Economics at the University of Sheffield and later worked in London as a secretary. Her interest in flying began after a visit to the Stag Lane Aerodrome, where she became captivated by the sight and sound of aircraft. This fascination quickly turned into a pursuit. She trained at the London Aeroplane Club and, in 1929, earned her pilot’s licence, quickly followed by an aircraft engineer’s licence – making her one of the first women in Britain to achieve this dual qualification. Her technical knowledge gave her a degree of independence and credibility in a male-dominated field.

Her most famous journey took place in May 1930, when she became the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia. Determined to make the 11,000-mile journey without the backing of major sponsors, Johnson purchased a second-hand de Havilland Gipsy Moth biplane, which she named Jason. The aircraft was small, had an open cockpit, and lacked modern navigation or safety equipment, making the journey extraordinarily perilous. Along the way, she faced sandstorms, monsoon rains, engine troubles, and the constant risk of becoming lost.

The flight began on the 5th of May, 1930, from Croydon Airport and took her through Europe, the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia, before arriving in Darwin, Northern Territory, on the 24th of May. Although she did not beat the existing speed record, her solo journey captured the public imagination. She was hailed as a national heroine, with thousands gathering to see her at public appearances following her return to Britain. Her courage and individualism came to represent the spirit of adventure in the interwar period.

Following this achievement, Johnson continued to push the boundaries of aviation. She undertook several record-breaking flights, often with her husband, fellow pilot Jim Mollison, whom she married in 1932. That same year, the pair flew non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean in a de Havilland Dragon aircraft, setting a new record for the first such crossing by a married couple. Johnson also attempted to break the London-to-Cape Town record, though she faced setbacks due to mechanical issues and weather challenges.

Her career was not without danger. Aviation in the 1930s was fraught with risk, and Johnson experienced several crashes and forced landings. Yet she remained undeterred, demonstrating a tenacity and passion that earned her numerous awards, including the Harmon Trophy and a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1930.

When the Second World War began, Johnson offered her skills in service to her country. She joined the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a civilian organisation that ferried aircraft from factories to Royal Air Force bases. This work was vital but hazardous, as pilots often flew without weapons or radios, in all weather conditions. On the 5th January, 1941, Johnson’s life came to a tragic end. While ferrying an Airspeed Oxford aircraft in poor weather, she was last seen parachuting into the Thames Estuary after apparently running out of fuel or becoming disoriented. Despite rescue attempts, she drowned, and her body was never recovered.