On the 12th of February, 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, was exiled from the Soviet Union. Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) was one of the most formidable moral and literary voices of the twentieth century. A novelist, historian, and dissident, he transformed personal suffering into a vast indictment of totalitarianism, particularly the Soviet system of repression. His work not only exposed the hidden machinery of the Gulag labour camps but also forced the world to confront the human cost of ideological tyranny.

Solzhenitsyn was born on the 11th of December, 1918, in Kislovodsk, southern Russia, shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution. His father had died in a hunting accident before his birth, and he was raised by his mother in modest circumstances. A gifted student, Solzhenitsyn studied mathematics and physics at Rostov University, while also pursuing a deep interest in literature and Russian history. Like many young intellectuals of his generation, he initially embraced Marxism and the promises of the Soviet state, a faith that would be brutally shattered by experience.

During the Second World War, Solzhenitsyn served as an artillery officer in the Red Army and was decorated for bravery. In 1945, however, he was arrested after private letters to a friend were intercepted by Soviet censors. In them, he had criticised Joseph Stalin and questioned the direction of the regime. For this offence he was sentenced to eight years in labour camps, followed by internal exile. This period—years of hard labour, hunger, illness, and constant surveillance—became the crucible in which his later literary work was forged.

After his release and rehabilitation following Stalin’s death, Solzhenitsyn began writing in earnest. His breakthrough came in 1962 with One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a stark, restrained account of a single day in a labour camp. Remarkably, it was published with official approval during Nikita Khrushchev’s brief period of de-Stalinisation. The novella caused a sensation, both in the Soviet Union and abroad, as it shattered the silence surrounding the Gulag while maintaining an understated, almost documentary tone. It established Solzhenitsyn as a writer of immense moral authority.

As the political climate hardened again, Solzhenitsyn’s relationship with the Soviet state deteriorated. His subsequent works—The First Circle, Cancer Ward, and most explosively The Gulag Archipelago—could no longer be published legally at home. The Gulag Archipelago, released in the West in 1973, was neither novel nor conventional history, but a vast mosaic of testimony, memoir, and analysis. Drawing on hundreds of survivor accounts, it demonstrated that the camp system was not an aberration but a central pillar of Soviet power. The book profoundly altered Western perceptions of communism and stands as one of the most influential works of the century.

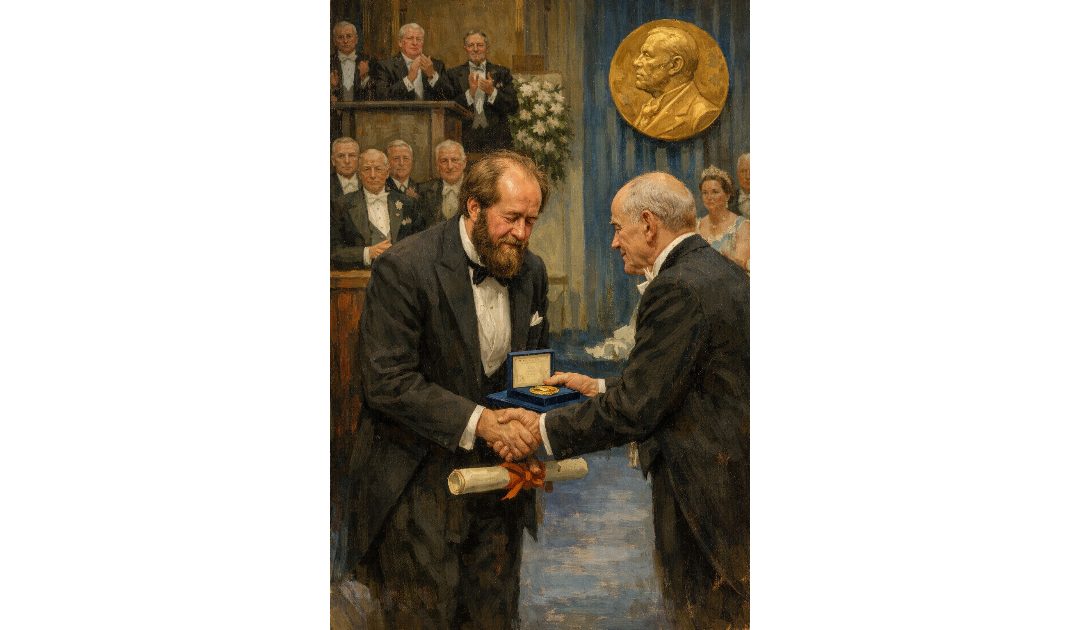

In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.” Fearing he would be prevented from returning, he did not attend the ceremony until years later. In 1974, Soviet authorities arrested him, stripped him of his citizenship, and expelled him from the country. He eventually settled in the United States, living for many years in relative isolation in rural Vermont.

Exile did not soften Solzhenitsyn’s views, but it complicated his reputation. While he remained a fierce critic of Soviet totalitarianism, he also became increasingly critical of Western materialism, secularism, and what he saw as moral decline. His 1978 Harvard commencement address, in which he warned that the West had lost courage and spiritual depth, was widely discussed and often misunderstood. To some, he appeared reactionary or austere; to others, he was a prophet speaking uncomfortable truths.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia in 1994. He was greeted with respect but also controversy, as post-Soviet society struggled to reconcile his moral vision with the realities of modern Russia. In his later years, he continued to write essays and historical works, maintaining his belief in a Russia rooted in moral responsibility, cultural memory, and spiritual renewal.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn died in 2008, leaving behind a body of work that permanently altered the moral landscape of literature and history. He demonstrated that the written word could confront vast systems of oppression and restore dignity to millions of silenced voices. Whether admired, disputed, or resisted, his legacy endures as a testament to the power of truth told at great personal cost.