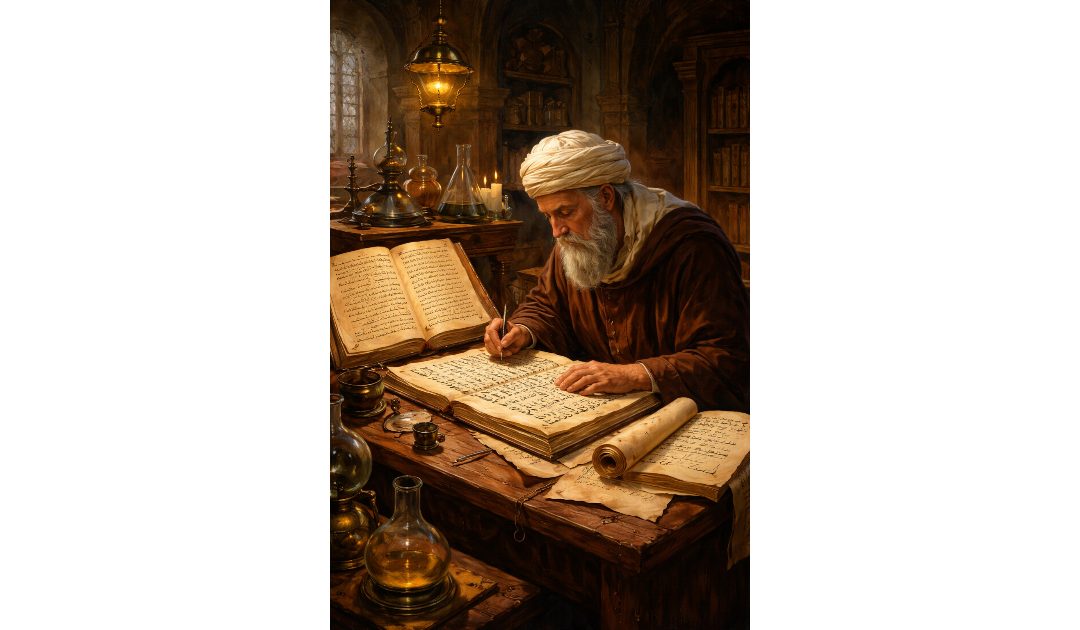

On the 11th of February, 1144, Robert of Chester completed the translation from Arabic into Latin of Testamenti Morieni, a textbook on alchemy. Alchemy in medieval Europe was not merely a proto-chemistry obsessed with gold-making, but a rich intellectual tradition that blended natural philosophy, cosmology, theology, and practical experiment. One of the most important conduits through which alchemical knowledge entered Latin Christendom was translation from Arabic sources during the twelfth century. Among the earliest and most influential of these translations was the Testamentum Morieni (Testamenti Morieni), rendered into Latin around 1144 by Robert of Chester—also known in some sources as Robert of Leicester. This work played a foundational role in shaping European alchemy for centuries.

Alchemy itself developed in the Hellenistic world, particularly in Egypt, where Greek philosophical ideas were combined with Egyptian metallurgical practices and religious symbolism. Late antique alchemists such as Zosimos of Panopolis framed the transformation of metals as both a material and a spiritual process, involving purification, death, and rebirth. These ideas were preserved and expanded in the Islamic world after the decline of classical institutions in Western Europe. Arabic alchemists such as Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Geber) and al-Rāzī refined experimental techniques, developed systematic theories of matter, and embedded alchemy within Aristotelian natural philosophy.

By the twelfth century, Latin Europe was beginning to rediscover this lost corpus of scientific and philosophical knowledge. Translation centres in places such as Toledo, Palermo, and the Crusader states facilitated contact between Arabic, Greek, and Latin intellectual traditions. Robert of Chester was one of the most significant translators of this movement. An English scholar working in Islamic Spain, he translated a wide range of texts, including the Qur’an (the first complete Latin translation), astronomical works, and several treatises on alchemy.

The Testamentum Morieni is traditionally presented as a dialogue between Morienus Romanus, a legendary Alexandrian hermit-alchemist, and the Umayyad prince Khālid ibn Yazīd. Although the historical reality of these figures is doubtful, the text carries immense symbolic authority. Morienus is portrayed as the last heir of ancient Greek alchemical wisdom, passing his knowledge to the Islamic world, which in turn transmits it to Latin Christendom through translation. This framing reinforced the idea of alchemy as an ancient, secret wisdom handed down through a chain of initiates.

Robert’s Latin translation introduced European readers to a coherent vision of alchemy centred on the lapis philosophorum, the Philosopher’s Stone. The text emphasises that true alchemy is not a vulgar craft but a divine science, requiring moral purity, patience, and obedience to natural processes. It stresses the unity of matter: all metals are composed of the same fundamental substance and differ only in their degree of perfection. Transmutation, therefore, is possible through the correct manipulation of nature, not through trickery or deception.

One of the most significant influences of the Testamentum Morieni was its articulation of alchemy as a spiritual discipline as much as a technical one. The language of the text is steeped in allegory, warning against literal-minded interpretation. Fire, for example, is not merely physical heat but a symbol of the inner transformative power that perfects matter. This approach resonated strongly with medieval Christian thinkers, who were accustomed to reading Scripture allegorically and saw no contradiction in interpreting natural processes in moral and spiritual terms.

The translation also helped establish a distinctive alchemical vocabulary in Latin. Terms relating to sublimation, coagulation, solution, and fixation entered European discourse through works like the Testamentum Morieni. Later alchemists such as Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, and Pseudo-Geber drew upon this lexicon, even when they moved in more experimental or systematic directions. The authority of the text was such that it was frequently cited, paraphrased, and glossed throughout the later Middle Ages.

Equally important was the way Robert’s translation framed alchemy as legitimate natural philosophy rather than illicit magic. By presenting the art as ancient, rational, and grounded in observation of nature, the Testamentum Morieni helped alchemy gain a foothold in monastic libraries and scholarly circles. This legitimacy was crucial at a time when suspicion of occult practices could easily lead to accusations of heresy or sorcery.

In the long term, the influence of Robert of Chester’s translation extended beyond medieval alchemy into early modern thought. Renaissance alchemists such as Paracelsus and later Rosicrucian writers inherited the idea of alchemy as a total philosophy of nature and spirit—a conception traceable in part to the Testamentum Morieni. Even as alchemy gradually gave way to modern chemistry, its symbolic language and vision of transformation continued to shape Western esoteric and scientific imagination.