Grand Central Terminal in New York City opened on the 2nd of February, 1913. Claire and I want to cross the Atlantic on the Queen Mary II. In fact we bought tickets to do the round trip with an afternoon in New York, but then Covid struck and we got a refund. We still want to do it, but not until President Trump has gone. We would then, perhaps, see more of the US. Possibly by train from Grand Central.

Grand Central Terminal is one of New York City’s most enduring landmarks, a monument not only to transportation but to the ambition, optimism, and engineering prowess of the United States in the early twentieth century. Its history reflects the transformation of New York from a railroad city of steam and soot into a modern metropolis shaped by electrification, urban planning, and architectural grandeur.

The story of Grand Central begins in the nineteenth century, when railroads were rapidly expanding and Manhattan struggled to accommodate them. In 1871, Cornelius Vanderbilt opened Grand Central Depot at 42nd Street, designed by John B. Snook. At the time, the location was far north of the city’s commercial core, but Vanderbilt foresaw that New York would grow northward. The depot consolidated several rail lines that previously terminated elsewhere, helping to tame the chaos of competing railroad companies. However, the depot was designed for steam locomotives, which produced smoke, noise, and frequent accidents.

By the end of the century, these problems had become intolerable. A deadly collision in 1902 inside the Park Avenue tunnel, caused by smoke-obscured signals, catalysed change. Public outrage and new city regulations effectively banned steam locomotives south of the Harlem River. This forced the New York Central Railroad to rethink its entire terminal and approach to rail transport. The solution lay in electrification, which allowed trains to operate cleanly underground and freed valuable surface land for development.

In 1903, plans were announced for an entirely new terminal, far larger and more ambitious than anything before it. The architectural firm Reed & Stem, working with Warren & Wetmore, designed the building in the fashionable Beaux-Arts style, inspired by European classical architecture. Construction began in 1903 and took nearly a decade, requiring the excavation of millions of cubic yards of earth and the creation of a vast, multi-level system of tracks and platforms beneath the city. This was an unprecedented engineering feat, allowing suburban and long-distance trains to operate efficiently below ground.

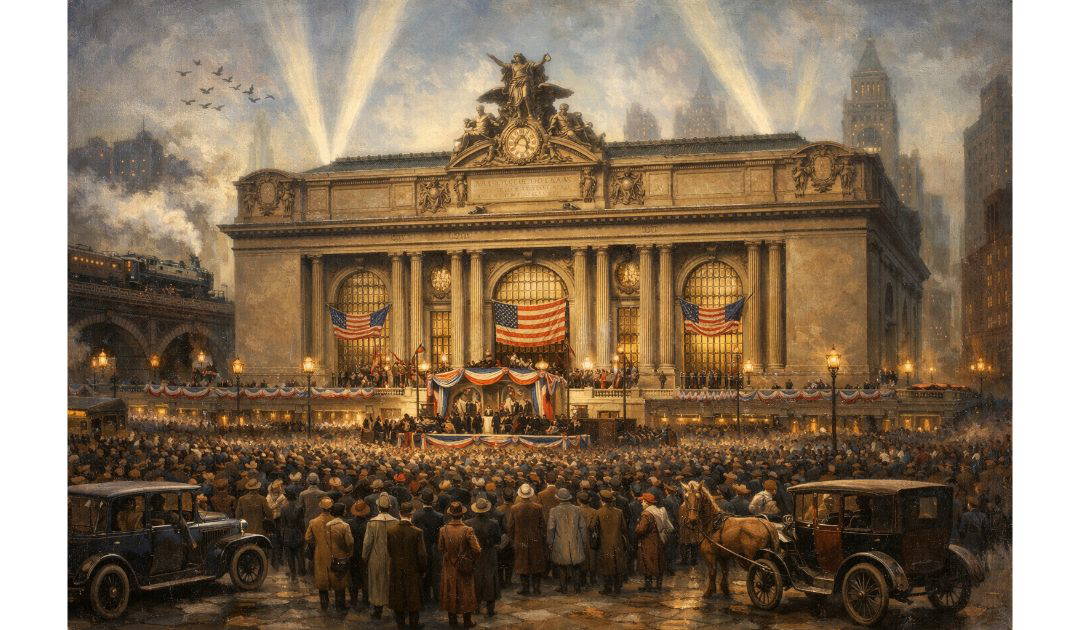

Grand Central Terminal officially opened on the 2nd of February, 1913, and it immediately captured the public imagination. Its monumental façade on 42nd Street, crowned by Jules-Félix Coutan’s sculptural group depicting Mercury, Minerva, and Hercules around a massive clock, proclaimed the building as a civic temple to movement and commerce. Inside, the Main Concourse astonished visitors with its soaring vault, celestial ceiling, and expansive sense of space. The terminal was designed not merely as a transit hub, but as an experience—one that celebrated travel as a grand, almost ceremonial act.

Crucially, Grand Central was also a real estate project. The decision to bury the tracks enabled the development of “Terminal City,” a coordinated district of hotels, office buildings, and clubs around the terminal, including the Commodore Hotel (now the Grand Hyatt). This approach helped shape modern Midtown Manhattan and demonstrated how infrastructure could drive urban growth.

For several decades, Grand Central thrived as a symbol of American modernity. However, after the Second World War, the rise of automobiles, highways, and air travel led to a steep decline in passenger rail use. By the 1950s and 1960s, the terminal was in visible decay. Commercial pressures mounted, and parts of the building were altered insensitively. The most serious threat came in the late 1960s, when the owners proposed demolishing the terminal and replacing it with a skyscraper.

The fight to save Grand Central became a landmark moment in the preservation movement. Led by figures such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, campaigners argued that the terminal was not merely real estate but a cultural treasure. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Law, ruling in favour of protecting Grand Central. This decision set a powerful precedent for historic preservation across the United States.

In the late twentieth century, Grand Central underwent a meticulous restoration. Completed in the 1990s, the project cleaned decades of grime from the stonework, restored the celestial ceiling to its original brilliance, and revitalised public spaces while accommodating modern needs. The terminal emerged once more as both a working transportation hub and a beloved civic space.

Today, Grand Central Terminal stands as a living piece of history. It is used daily by hundreds of thousands of commuters, yet it also functions as a symbol of New York’s resilience and capacity for reinvention. More than a station, it is a testament to the idea that infrastructure can be beautiful, humane, and enduring—an urban cathedral where movement, memory, and architecture converge.