On the 20th of January, 1649, proceedings began in the High Court of Justice in the trial of King Charles I. Charles was not born to be king, but his elder brother Henry Frederick died of typhoid, at the age of 18, in 1612. In addition to succeeding Henry as king, Charles replaced him in betrothal to Henrietta Maria, daughter of Marie de Medici, as related in Serpent’s Teeth, the fifth book in the Sir Anthony Standen Adventures. I am currently seeking a publisher, but if unsuccessful will publish on KDP.

Charles I’s path to the scaffold began long before his arrest. His belief in the divine right of kings brought him into repeated conflict with Parliament, particularly over taxation, religion, and the extent of royal authority. Charles ruled without Parliament for eleven years (1629–1640), raising funds through controversial means such as ship money and enforcing religious policies that alienated both Puritans and Scots. When rebellion in Scotland forced him to recall Parliament, tensions escalated into open war in 1642 between Royalists and Parliamentarians.

The civil wars ended decisively in Parliament’s favour by 1646, but peace proved elusive. Charles, instead of negotiating sincerely, sought to exploit divisions among his enemies and even encouraged a second civil war in 1648. This convinced many in the New Model Army that the king could never be trusted and that lasting peace required his removal. The army, led politically by figures such as Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton, purged Parliament in December 1648, excluding members willing to compromise with the king. The resulting “Rump Parliament” resolved to put Charles on trial.

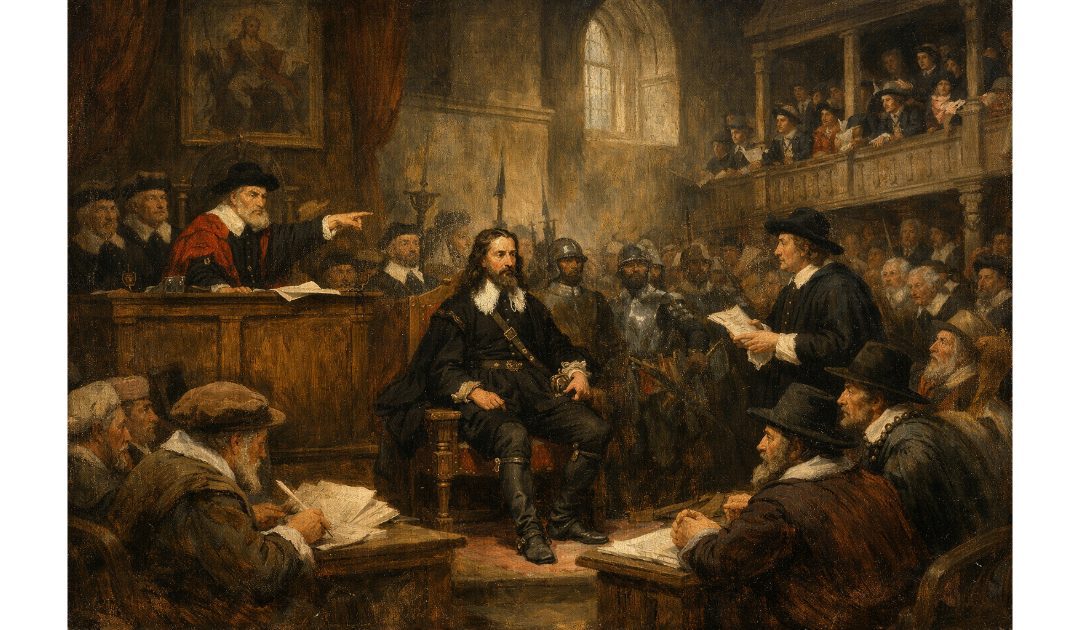

The High Court of Justice was established by an act of the Rump Parliament, despite the House of Lords’ refusal to consent—already a sign of the revolutionary nature of the proceedings. The court comprised around 135 commissioners, though fewer than 70 ever attended regularly. John Bradshaw, a relatively obscure lawyer, was appointed president. The charge against Charles was that he had committed treason against the people of England by waging war against his own subjects—a startling inversion of traditional legal doctrine, which held that treason was a crime against the king, not committed by him.

The trial opened on the 20th of January 1649 in Westminster Hall, a vast and symbolically charged space. Charles appeared calm and dignified, dressed in black and sitting defiantly as the charges were read. From the outset, he challenged the court’s legitimacy, repeatedly asking by what lawful authority he was being tried. Since English law recognised no court superior to the king, Charles argued that the proceedings were illegal and therefore invalid. He refused to enter a plea, believing that to do so would acknowledge the court’s authority.

Bradshaw and the commissioners pressed on regardless. Witnesses testified to Charles’s role in initiating and sustaining the civil wars, though the king was denied the opportunity to cross-examine them. The court ruled that his refusal to plead amounted to a confession of guilt. To supporters of the trial, this was a necessary step to bring a tyrant to justice; to its critics, then and since, it was a deeply flawed and politically driven process.

On the 27th of January, 1649, the court found Charles guilty and sentenced him to death. Only 59 commissioners signed the death warrant, a telling indication of lingering unease even among his judges. Three days later, on the 30th of January, Charles I was executed outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall. He met his death with composure, declaring himself a martyr for lawful monarchy—a claim that would resonate powerfully with Royalist supporters and help shape his posthumous reputation.

The trial and execution of Charles I abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, ushering in the Commonwealth of England. Though the republic would last little more than a decade, the trial’s legacy endured. It demonstrated that a king could be held accountable by his people, a notion that would echo through later constitutional developments in Britain and beyond, even as the monarchy itself was restored in 1660.