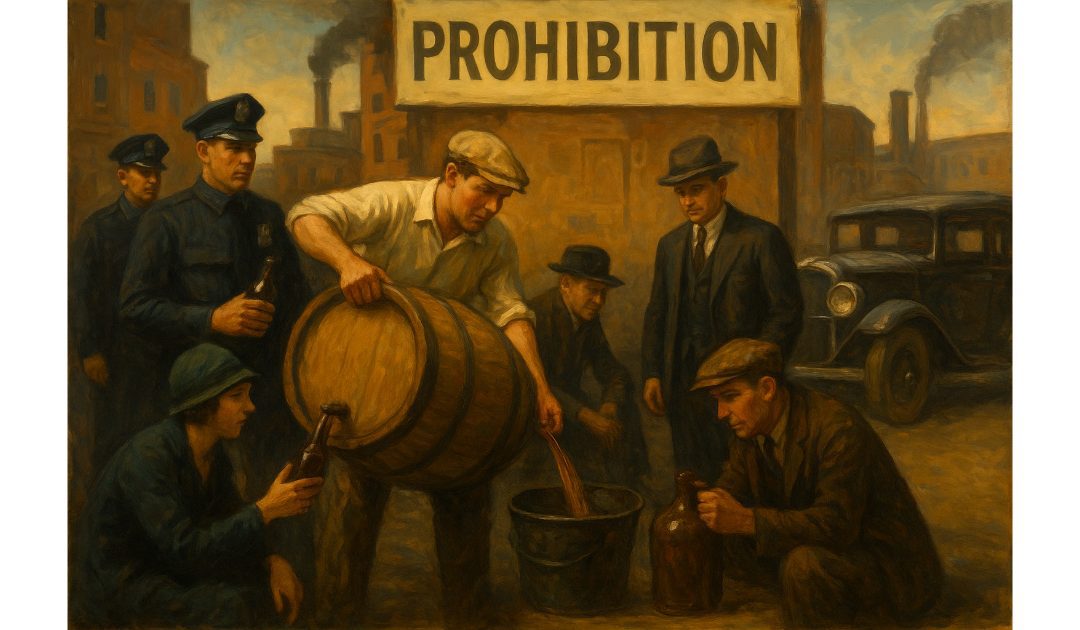

On the 17th of January, 1920, the Volstead Act came into effect in the United States of America introducing the prohibition of alcohol. The Volstead Act, formally known as the National Prohibition Act of 1919, was the legislative backbone of America’s great national experiment with banning alcohol. While the Eighteenth Amendment had already prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transport of intoxicating liquors, the amendment itself was brief and vague. It required a comprehensive federal law to define what “intoxicating liquors” meant, set out enforcement mechanisms, and establish the penalties for violations. The Volstead Act provided all of that, shaping American society, crime, politics, and culture throughout the 1920s.

The Act was named for Andrew Volstead, a Republican congressman from Minnesota who chaired the House Judiciary Committee. Although Volstead lent his name to the bill, he was not its principal architect. The driving force came instead from the Anti-Saloon League, particularly its general counsel, Wayne B. Wheeler, one of the most influential and relentless lobbyists of the era. Wheeler believed that alcohol was the root of social decay—fueling domestic violence, poverty, political corruption, and moral decline. His organisation exerted immense pressure on Congress and state legislatures, and by 1919, with wartime patriotism amplifying the perceived need for national discipline, prohibitionist sentiment had reached its peak.

The Act defined any beverage containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol by volume as intoxicating, a threshold far stricter than many Americans had expected. Beer and wine, long consumed with relative moderation, now fell under the same ban as whiskey and gin. This definition ignited immediate resentment, particularly among immigrant communities—Germans, Italians, Irish, and others—who viewed beer and wine as cultural staples rather than social threats.

Under the Act, the Department of the Treasury was tasked with enforcement, a decision that would prove problematic. Treasury agents were few in number, often poorly trained, and sometimes tempted by bribes in an environment teeming with opportunities for corruption. Enforcement required constant vigilance: shutting down illegal stills, raiding warehouses, seizing shipments, and monitoring borders and coastlines. The cost was immense, and the results were uneven across the country. Rural and Protestant regions tended to support Prohibition and enforce it more vigorously, while cities—especially port cities and industrial centres—became hotbeds of resistance.

One of the most significant unintended consequences of the Volstead Act was the explosive growth of organised crime. Prohibition created a vast black market for alcohol, enriching gangsters who were quick to capitalise on the public’s ongoing desire for drink. Figures such as Al Capone in Chicago built empires based on smuggling, distribution, and the operation of clandestine bars known as speakeasies. These establishments flourished—estimates suggest there were far more drinking spots during Prohibition than before it. Corruption spread rapidly, with police officers, judges, and politicians susceptible to bribery. Violence escalated as rival gangs fought over territory and supply routes, most infamously embodied in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929.

Yet Prohibition was not universally unpopular. Temperance advocates pointed to certain successes. Overall alcohol consumption did decline, at least initially, and some communities reported fewer alcohol-related hospitalisations and arrests. Employers noted reduced absenteeism. Many women’s organisations, which had been instrumental in the temperance movement, saw Prohibition as a victory for families and public morality.

However, the negative aspects increasingly outweighed the intended benefits. The production of dangerous homemade liquor, known as “moonshine” or “bathtub gin,” led to thousands of cases of poisoning, blindness, and death. The government’s own policy of denaturing industrial alcohol—to prevent it being diverted and consumed—only worsened this hazard. Meanwhile, respectable citizens routinely broke the law, fostering widespread cynicism and a sense that Prohibition had undermined respect for legal authority.

By the late 1920s, the tide had turned. The Great Depression intensified demands for repeal, as legalising alcohol promised tax revenue and job creation. Public sentiment shifted decisively. Political candidates, most notably Franklin D. Roosevelt, campaigned openly for an end to Prohibition. Even former supporters of the Volstead Act acknowledged that the law had become unenforceable.

In 1933, the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified, repealing the Eighteenth Amendment and effectively nullifying the Volstead Act. It remains the only constitutional amendment ever overturned by another. States regained the authority to regulate alcohol as they saw fit, leading to a patchwork of local laws that persist today.

The Volstead Act stands as one of the most ambitious—and controversial—social experiments in American history. Though well-intentioned, it revealed the limits of legislating morality and the difficulty of suppressing deeply ingrained cultural habits. Its legacy is a powerful reminder that sweeping legal prohibitions can produce consequences far more complex than their architects ever imagined.