On the 16th of January, 1547, Grand Duke Ivan IV of Muscovy became the first Tsar of Russia.

Ivan’s early life was shaped by trauma and instability. Born to Grand Duke Vasily III and Elena Glinskaya, he inherited the throne at just three years old. When his mother died in 1538—probably poisoned—the young Ivan became a pawn in the ruthless power struggles among the boyar clans, notably the Shuiskys and Belskys. These years of neglect, humiliation, and violence profoundly scarred him. Ivan later recalled how nobles mocked him, beat his servants, and treated him with contempt; he remembered watching the boyars plunder the palace while he and his brother starved. This childhood chaos shaped his lifelong suspicion of the aristocracy and contributed to the fierce authoritarianism he would later impose.

Upon reaching maturity, Ivan sought to stabilise and elevate Muscovy. In 1547, at age sixteen, he staged a momentous ceremony in which he was crowned “Tsar”, a title derived from “Caesar,” signalling imperial ambition and divine authority. His early reign—often called the “Good Period”—showed promise. Supported by a reformist circle of advisers, sometimes known as the “Chosen Council,” Ivan embarked on a wide range of administrative, legal, and military reforms aimed at strengthening central power while improving governance.

One of the most notable achievements of this period was the Sudebnik of 1550, a revised law code that attempted to impose order, curtail corruption, and standardise legal procedures. Ivan also introduced the Zemsky Sobor, an assembly of nobles, townspeople, and clergy that functioned as a consultative body—unprecedented in Muscovite political life. His reforms extended to the Church, culminating in the Stoglavy Council of 1551, which standardised religious practices and asserted state influence over ecclesiastical affairs.

Militarily, Ivan oversaw dramatic territorial expansion. His most famous conquests were the Khanates of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556), which broke Tatar domination along the Volga and opened the way for Russian penetration into Siberia. These victories transformed Muscovy into a multiethnic empire and greatly enhanced Ivan’s prestige.

Yet this promising era gradually unravelled. The death of his beloved first wife, Anastasia Romanovna, in 1560, dealt a psychological blow from which Ivan never fully recovered. Convinced she had been poisoned by boyars—a belief unproven but persistent—he descended into paranoia and mistrust. The Livonian War (1558–1583), initiated with hopes of gaining access to the Baltic Sea, soon drained Muscovy’s resources and brought foreign enemies to its borders. Military setbacks, economic strain, and the loss of key advisers all inflamed Ivan’s insecurities.

In 1565 he launched the most infamous policy of his reign: the Oprichnina. Dividing the realm into two parts, Ivan ruled the Oprichnina directly with his personal corps of enforcers, the Oprichniki, who were granted sweeping powers to investigate, punish, confiscate, and terrorise. Dressed in black and riding black horses, bearing emblems of the dog’s head and broom (symbolising sniffing out treason and sweeping it away), they became agents of systematic repression.

The Oprichnina devastated Muscovy. Entire towns were depopulated, noble families executed or exiled, and estates confiscated. The most notorious episode occurred in Novgorod in 1570, where Ivan, convinced of treasonous ties with Lithuania, unleashed a massacre that killed thousands—clergy, merchants, and peasants alike. This period crippled the economy, eroded trust, and fractured the nobility, achieving short-term obedience at the cost of long-term instability.

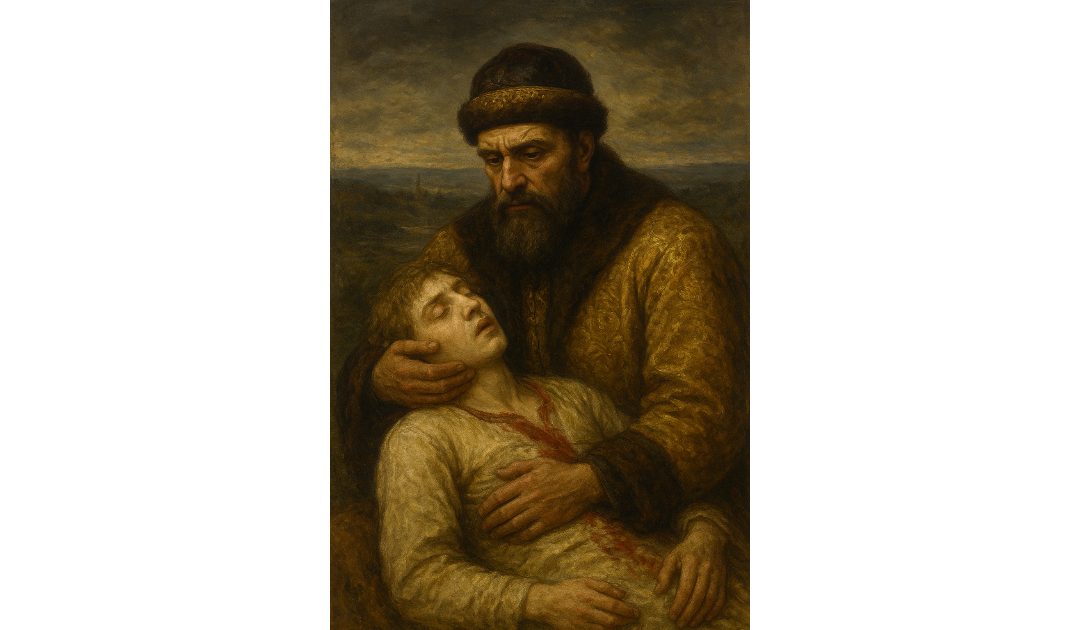

Ivan’s personal life was equally turbulent. He married at least eight times, often repudiating or abusing his wives. His volatile temper reached its tragic height in 1581 when, in a fit of rage, he struck his son and heir, Ivan Ivanovich, fatally wounding him. The image of the Tsar cradling his dying son has become an enduring symbol of his tormented rule.

Despite his brutality, Ivan was intelligent, educated, and deeply religious. He was a prolific writer, composing letters, theological reflections, and polemics. He surrounded himself at times with scholars and showed genuine interest in statecraft and theology. This duality—between a thoughtful ruler and a violent tyrant—makes him a uniquely complex figure.

When Ivan died in 1584, he left behind an expanded empire but also a weakened state, shattered elites, and a succession crisis that soon plunged Russia into the Time of Troubles. His reign remains a study in contrasts: visionary reform and catastrophic tyranny; imperial ambition and internal ruin; the forging of Russian autocracy and the destruction wrought by unchecked power.

Ivan IV endures as one of history’s archetypal tyrants, and as a ruler whose actions shaped the foundations of the Russian state for centuries to come.