On the 19th of December, 1783, William Pitt the Younger became the youngest Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at the age of 24.

William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806) was one of the most influential and remarkable figures in British political history. Born on 28 May 1759 in Hayes, Kent, he was the son of William Pitt the Elder, the celebrated Earl of Chatham and former Prime Minister, and Hester Grenville. Pitt the Younger grew up in a household steeped in politics and public service, and he inherited not only his father’s name but also his immense ambition and intellect. A prodigious child, he was privately educated due to frail health and by the age of fourteen entered Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he excelled in classics, history, and political philosophy. His exceptional ability in oratory and analysis prepared him for a career in Parliament, which began astonishingly early.

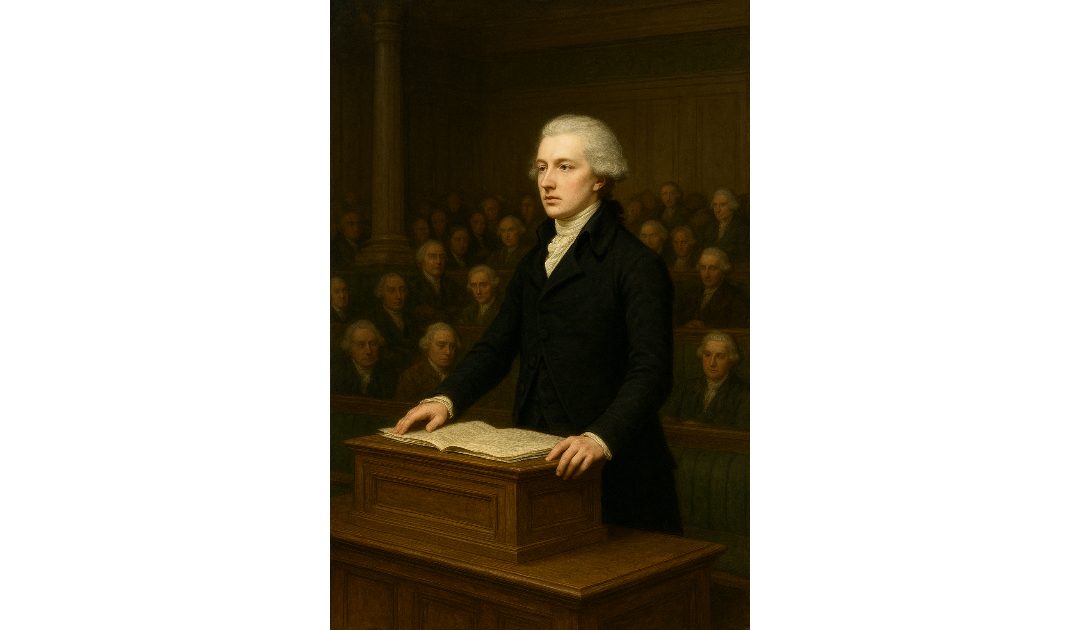

Pitt was elected to Parliament in 1781, at just twenty-one, as MP for Appleby. He quickly gained a reputation for his eloquence, clarity of thought, and financial expertise. Within two years, he became Chancellor of the Exchequer under the short-lived ministry of the Duke of Portland. However, his true rise to power came in December 1783, when King George III appointed him Prime Minister after the collapse of the Fox–North coalition. At only twenty-four, Pitt remains the youngest person ever to hold the office of Prime Minister, a fact that astonished contemporaries and earned him the nickname “the Boy Prime Minister.”

His early years in office were marked by political fragility. In 1784, he faced a hostile House of Commons but managed to survive long enough to call a general election, which he won decisively. This victory provided him with the parliamentary strength to begin implementing his reformist agenda. Pitt’s domestic achievements were significant. He worked to stabilise the nation’s finances, introducing measures to reduce the national debt and reform taxation. His creation of the Sinking Fund in 1786 was a key attempt to manage the debt left over from the American War of Independence. He also pushed for modest parliamentary reforms, such as reducing electoral corruption, though more ambitious measures were blocked.

Pitt’s tenure was dominated by foreign policy challenges, particularly the French Revolution and the wars that followed. Initially, he sought to maintain peace with revolutionary France, believing that Britain needed stability to continue its economic recovery. However, the radicalisation of the French Revolution and the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793 led Britain into war. Pitt became the architect of a series of coalitions against France, navigating the immense pressures of wartime governance. He expanded the Royal Navy, bolstered Britain’s fiscal capacity, and faced the spread of revolutionary ideas at home, responding with repressive measures such as the suspension of habeas corpus and laws against seditious meetings.

Pitt’s government also confronted Ireland’s increasingly turbulent political situation. The 1798 Irish Rebellion, fuelled by the influence of revolutionary France, highlighted the fragility of British rule in Ireland. Pitt concluded that the best solution was a formal union between Great Britain and Ireland, which he achieved with the Act of Union in 1801. Yet his hope to accompany the union with Catholic emancipation—allowing Catholics to sit in Parliament—was thwarted by King George III’s opposition, forcing Pitt to resign in 1801 on a matter of principle.

He returned to office in 1804, as Napoleon Bonaparte’s threat to British security grew. Pitt worked to form the Third Coalition against France, which culminated in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, a decisive naval victory securing Britain’s dominance at sea. Nevertheless, defeats in continental Europe weighed heavily on him. Pitt’s health, always delicate, deteriorated under the strain of war and political burdens.

William Pitt the Younger died on the 23rd of January, 1806, at the age of forty-six, worn out by the pressures of leadership. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, near his father. His legacy is one of financial prudence, administrative reform, and resolute wartime leadership. Though some criticised his reluctance to embrace more sweeping domestic reforms, his ability to stabilise the nation and guide Britain through perilous times secured his place as one of its greatest statesmen. Pitt’s career, beginning and ending in youth, symbolises both the promise and the costs of political genius in an era of upheaval.