Wikipaedia tells me that the first account of a blood transfusion was published as a letter from the physician Richard Lower to the chemist Robert Boyle on the 17th of December, 1665, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. I recently made my 16th donatation, so it caught my attention.

The history of blood transfusion is a fascinating journey that reflects centuries of medical curiosity, experimentation, and eventual mastery. From the earliest speculations about the life-giving properties of blood to the sophisticated transfusion practices of modern medicine, the story is one of trial, error, and innovation.

The concept of blood as a vital fluid stretches back to ancient civilisations. The Greeks and Egyptians believed that blood contained the essence of life, and some early medical texts suggest that blood-drinking rituals or the ingestion of animal blood could rejuvenate a person’s strength or youth. Although these practices were entirely without scientific basis, they reflect an essential insight: blood was central to life itself.

The first attempts at actual blood transfusion began in the 17th century, spurred by the scientific revolution and the discovery of blood circulation by William Harvey in 1628. Understanding that blood moved in a system of arteries and veins prompted ambitious physicians to speculate whether blood could be transferred from one individual to another. In 1665, the English physician Richard Lower conducted one of the first successful animal-to-animal transfusions, moving blood from one dog to another and observing that the recipient survived. This ground-breaking experiment inspired others to try similar techniques with humans.

By 1667, Jean-Baptiste Denis in France performed one of the earliest documented human transfusions. He transfused sheep’s blood into a teenage boy in an attempt to cure illness, and the boy survived. However, subsequent transfusions into other patients resulted in severe reactions, including death. These disastrous outcomes led to public outrage and legal prohibitions against the practice in France, England, and even the Papal States. Without an understanding of immune reactions or blood compatibility, early human transfusions were extremely risky.

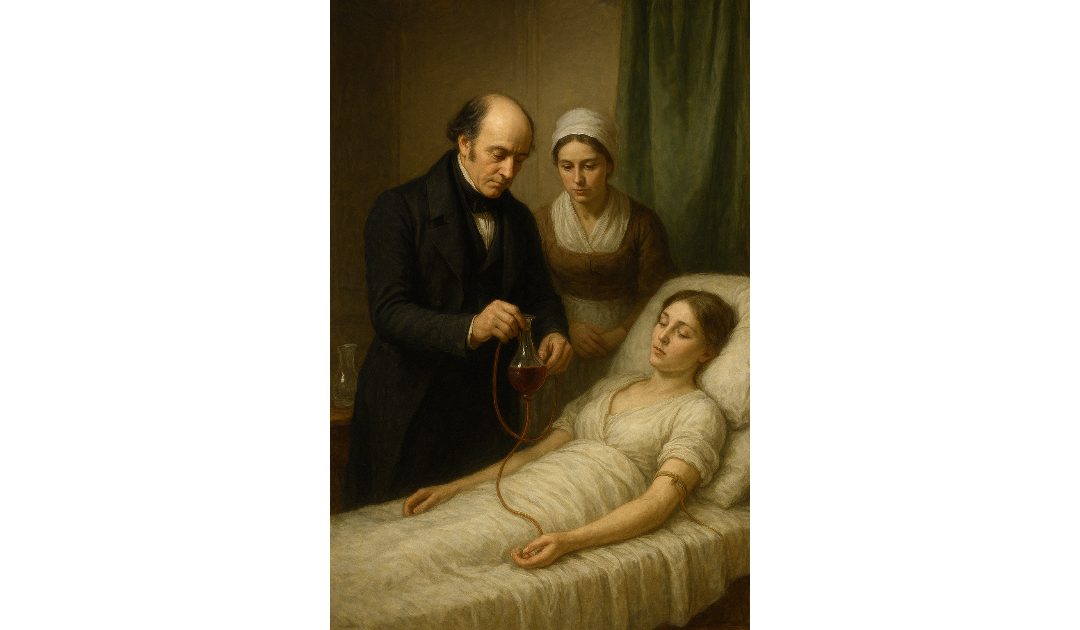

For over 150 years, the idea of blood transfusion remained largely dormant. It was not until the early 19th century, with advances in surgery and a better grasp of physiology, that the practice was cautiously revisited. In 1818, the British obstetrician James Blundell performed the first successful human-to-human transfusion to treat postpartum haemorrhage. Blundell understood that animal blood was probably incompatible with humans, and he developed rudimentary instruments to extract and inject human blood. Several of his patients survived, and his work laid the foundation for future transfusion medicine.

Despite Blundell’s pioneering efforts, blood transfusion remained unpredictable throughout the 19th century. Many patients died from haemolytic reactions because the underlying principle of blood compatibility was still unknown. It was the Austrian pathologist Karl Landsteiner who provided the crucial breakthrough in 1901, discovering the ABO blood group system. His work explained why some transfusions succeeded while others proved fatal: mismatched blood types led to immune reactions that destroyed the transfused blood cells. This discovery earned Landsteiner a Nobel Prize and transformed transfusion into a safer therapeutic procedure.

During the First World War, the need to treat wounded soldiers drove rapid innovation in transfusion techniques. The development of anticoagulants such as sodium citrate allowed blood to be stored briefly outside the body without clotting, enabling indirect transfusion from donor to patient. This period also saw the creation of the first rudimentary blood banks in field hospitals. By the Second World War, the organisation of large-scale blood donation drives, combined with improved storage techniques and the discovery of the Rhesus (Rh) factor in 1937, revolutionised transfusion medicine and saved countless lives.

The mid-20th century brought further refinements, including blood component therapy, in which whole blood could be separated into plasma, red cells, platelets, and clotting factors. This innovation allowed more efficient use of donations and tailored treatment for specific medical needs. By the latter half of the century, transfusion had become a standard, routine procedure in surgery, trauma care, and chronic disease management.

Today, blood transfusion is a highly regulated, scientific process supported by sophisticated testing, storage, and cross-matching techniques that minimise risk and maximise safety. The historical journey from mystical blood rituals to evidence-based transfusion medicine highlights the profound progress of medical science and the enduring importance of curiosity and careful experimentation in the pursuit of life-saving knowledge.

Blood is a theme in Called to Account, the fourth book in the Sir Anthony Standen Adventures.