The Royal Society, formally known as The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is one of the oldest and most prestigious scientific institutions in the world. It was founded in 1660 during a period of profound intellectual transformation often referred to as the Scientific Revolution. Its origins can be traced to an informal network of scholars, natural philosophers, and experimentalists who were seeking to explore the natural world through observation, experimentation, and rational inquiry, rather than relying solely on classical texts or religious doctrine.

The seeds of the Royal Society were sown in the early 1640s and 1650s, when small groups of scientifically minded individuals began to meet in London and Oxford. These gatherings became known as the “Invisible College,” a term which captured the idea of an informal community of like-minded thinkers. Among its early members were figures such as Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle, John Wilkins, and William Petty, each of whom was deeply engaged in experimenting with natural phenomena and questioning established beliefs. The political turbulence of the English Civil War slowed the organisation of a formal body, but the intellectual momentum continued to grow.

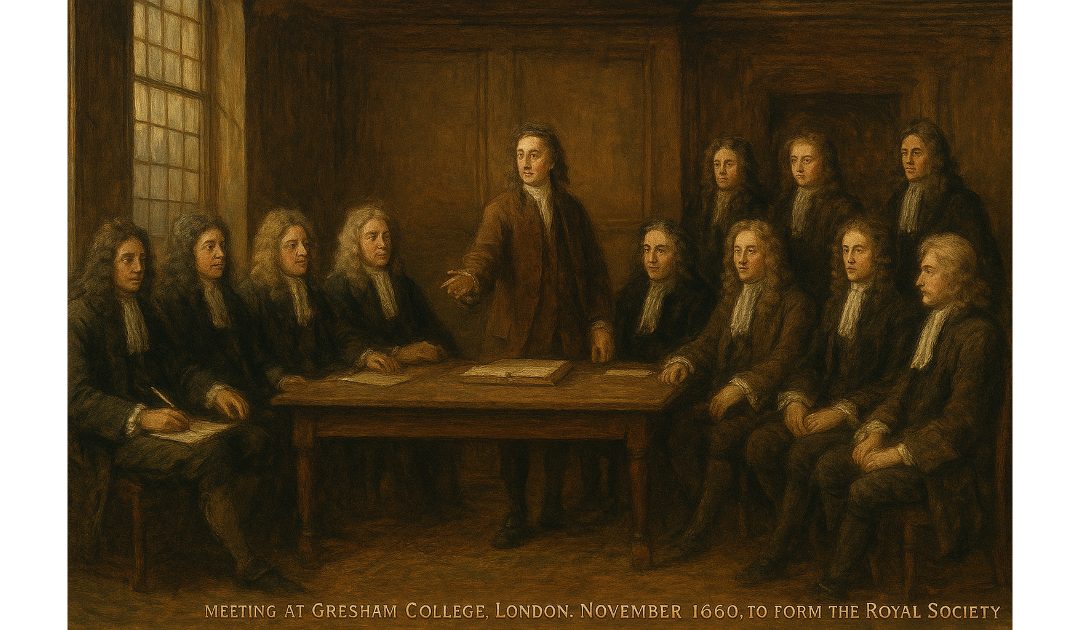

The decisive moment came on the 28th of November, 1660, following a lecture by Christopher Wren at Gresham College in London. A group of twelve men resolved to form a society devoted to the advancement of natural knowledge through experimental methods. Within two years, King Charles II—himself interested in scientific ideas—granted the society a Royal Charter, formally establishing it as The Royal Society of London. This official recognition gave the society legitimacy and a platform from which to expand its influence, as well as the protection of royal patronage.

In its early years, the Royal Society became famous for its commitment to empirical investigation and the exchange of scientific knowledge. Meetings were conducted in a spirit of collegial inquiry, with members demonstrating experiments, discussing observations, and proposing new avenues of research. The society’s motto, “Nullius in verba,” meaning “Take nobody’s word for it,” encapsulated its rejection of untested authority and its embrace of evidence-based science. The society also began publishing Philosophical Transactions in 1665, which remains the world’s longest-running scientific journal. This publication provided a formal mechanism for sharing discoveries and established the peer-to-peer communication model that underpins modern science.

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Royal Society nurtured some of the most influential scientific work in history. Fellows of the society included Isaac Newton, who revolutionised mathematics and physics, Edmund Halley, who predicted the return of his eponymous comet, and Robert Hooke, whose observations in microscopy opened new worlds of understanding. The society was not simply an academic gathering; it functioned as a hub for the accumulation of knowledge that could have practical applications in navigation, engineering, and medicine, reflecting the close relationship between scientific endeavour and the development of trade and empire.

Over time, the Royal Society evolved from a small, elite circle into a broader institution reflecting the professionalisation and expansion of science. In the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution transformed Britain, the society adapted to accommodate a growing and increasingly specialised scientific community. By this period, the society was no longer the sole focal point for scientific research in Britain, as universities, observatories, and laboratories proliferated, yet it retained a unique prestige as a national academy of science.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the Royal Society has continued to evolve in response to the changing nature of scientific activity. It has become more international in its outlook, fostering collaboration with scientists worldwide and promoting open access to scientific knowledge. The society also embraced a role in advising government and the public on issues of science policy, ethics, and education. While the early fellows were exclusively male and mostly drawn from the elite, the society has in recent decades made significant strides towards inclusivity, actively electing women and promoting diversity in scientific research.

Today, the Royal Society supports research through grants and fellowships, recognises outstanding contributions through medals and prizes, and engages the public in understanding science’s impact on society. It remains a forum for debate and the dissemination of knowledge, committed to the principles of evidence and inquiry that inspired its founders over three and a half centuries ago. From its origins as an intimate gathering of experimental philosophers in Restoration London to its status as a global leader in science, the Royal Society reflects both the continuity and the transformation of scientific endeavour. Its history is a testament to the enduring value of curiosity, collaboration, and the pursuit of knowledge for the benefit of humanity.