The second relief of Lucknow on the 16th of November, 1857, holds the record for the most Victoria Crosses awarded in a single day. Twenty-three were awarded for valour at the second relief of Lucknow, and one at an action south of Delhi.

The Second Relief of Lucknow was a pivotal episode during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, often referred to as the First War of Independence in India or the Sepoy Mutiny. It took place in the broader context of the Siege of Lucknow, one of the most dramatic and drawn‑out confrontations of the conflict. The second relief, occurring in November 1857, represented the concerted effort by the British to break the siege and rescue the garrison and civilians trapped in the Residency.

The rebellion had begun in May 1857 at Meerut and spread rapidly across northern India, driven by widespread discontent among Indian soldiers (sepoys) and civilians against the East India Company. In Lucknow, the capital of the province of Awadh (Oudh), British forces and loyalists had retreated into the fortified Residency compound when the uprising escalated in June 1857. The Residency sheltered British troops, their families, civilians, and local supporters, facing heavy attacks from rebel forces who vastly outnumbered them. The defenders endured months of bombardment, disease, and severe shortages, with morale under constant strain.

The first relief of Lucknow had taken place in late September 1857, led by Major General Sir Henry Havelock and reinforced by Sir James Outram. Havelock had fought several hard battles en route to the city, including at Cawnpore and Bithur, and finally reached the Residency on the 25th of September. However, this first relief was not a complete lifting of the siege. Though Havelock and Outram succeeded in reinforcing the garrison, they themselves became trapped within the Residency’s defences. Their arrival provided temporary respite and improved morale but offered no escape for those inside. The city and its approaches remained under rebel control.

By October 1857, the British command recognised the urgent need for a larger operation capable of not only relieving the garrison but also securing a safe withdrawal or establishing a sustainable hold in the city. The task fell to Sir Colin Campbell, newly appointed Commander‑in‑Chief in India. Campbell assembled a formidable relief column, drawing from regiments of British and loyal Indian troops, including the 93rd Highlanders, the 53rd Regiment, detachments of the 4th Punjab Rifles, and elements of the Naval Brigade with heavy guns. An advance base was established at Cawnpore to facilitate logistics and communications.

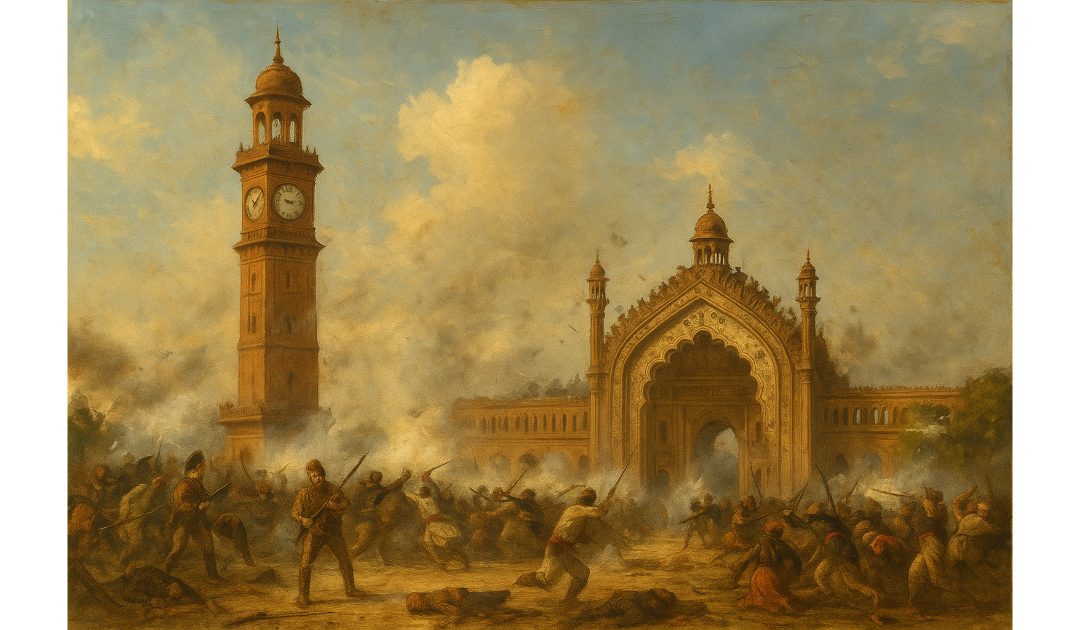

The second relief operation commenced in mid‑November 1857. Campbell approached Lucknow cautiously, mindful of the rebel strength and the difficulties of urban warfare. He opted to advance along the southern bank of the Gumti River, utilising the open countryside to minimise exposure to enemy fire from the city’s defences. On the 16th of November his forces engaged in the Battle of Secundra Bagh, a walled garden holding several thousand rebel defenders. After a fierce assault, the 93rd Highlanders and the 4th Punjab Rifles stormed the enclosure, resulting in heavy rebel casualties and opening the way towards the Residency.

Another key action took place at the Shah Najaf mosque, a formidable defensive position. The British artillery bombarded the structure, but its thick walls resisted heavy fire. Infantry assaults followed, with determined fighting before the defenders were overcome. These victories allowed Campbell’s column to push closer to the Residency, eventually linking up with the besieged garrison on the 17th of November. This successful junction marked the essence of the Second Relief of Lucknow.

After securing the connection, Campbell faced a strategic choice. Rather than attempting to hold the Residency indefinitely against superior rebel numbers, he opted to evacuate the garrison and non‑combatants. Over the following days, a carefully managed withdrawal took place, with women, children, and the wounded transported across the river to safety. By the end of November, the bulk of the garrison had successfully left Lucknow and moved to the British stronghold at Alambagh, south of the city. The Residency, though no longer inhabited, symbolised both the endurance of its defenders and the high cost of the siege.

The Second Relief of Lucknow had profound implications. It preserved a significant portion of the British forces and civilians, preventing a catastrophe that might have emboldened the rebellion further. It also demonstrated the effectiveness of methodical, well‑coordinated British military operations under Colin Campbell, contrasting with the desperate improvisation of the earlier relief. Nonetheless, the city of Lucknow itself remained in rebel hands until March 1858, when a full‑scale reconquest was undertaken.

The Second Relief of Lucknow is remembered both as an act of courage and as a symbol of the colonial struggle to maintain control during a major uprising. It encapsulates the heroism and suffering of those involved, the strategic calculations of imperial command, and the enduring legacies of the rebellion in shaping the course of British rule in India.

The Second Relief of Lucknow was a pivotal episode during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, often referred to as the First War of Independence in India or the Sepoy Mutiny. It took place in the broader context of the Siege of Lucknow, one of the most dramatic and drawn‑out confrontations of the conflict. The second relief, occurring in November 1857, represented the concerted effort by the British to break the siege and rescue the garrison and civilians trapped in the Residency.