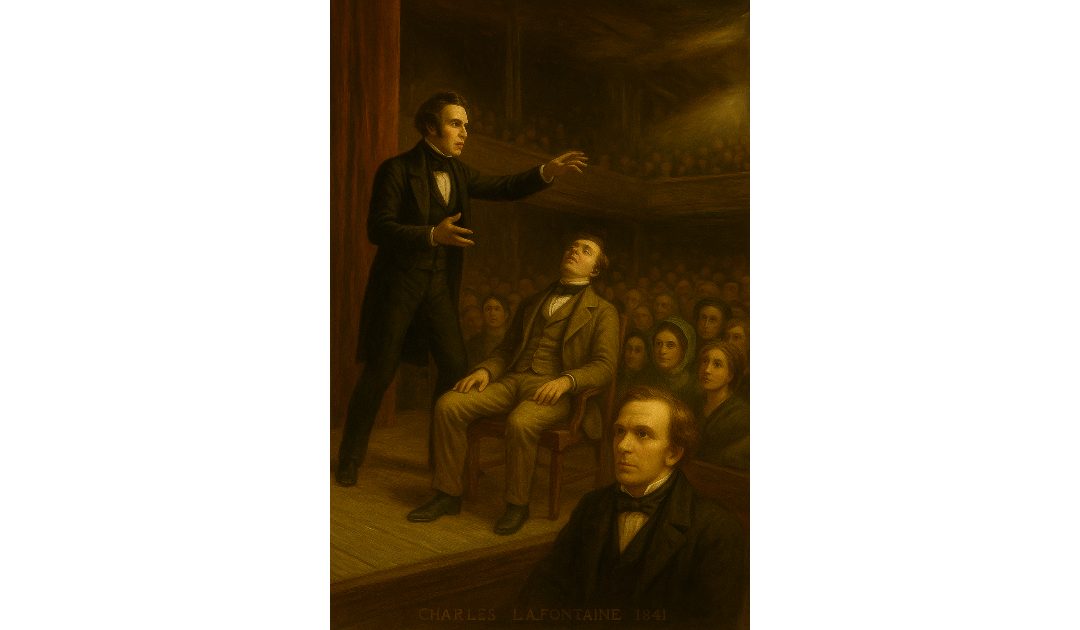

When I saw James Braid crop up in Wikipedia’s list for the 13th of November my immediate thought was of the golfer, one of the Great Triumvirate, with Harry Vardon and John Henry Taylor. But this James Braid saw a demonstration of animal magnetism by Charles Lafontaine which Taylor then studied and renamed as hypnotism. I have been fascinated by hypnotism since I saw a performance by a stage hypnotist at the Oxford Union in 1979. I introduced a form of hypnotism into The Suggested Assassin, the third book in the Sir Anthony Standen Adventures. As James Braid didn’t get involved until 1841, I called it induction.

James Braid (1795–1860) was a Scottish surgeon who is widely recognised as the father of modern hypnotism. His work in the mid-nineteenth century transformed the popular and often mystical conception of mesmerism into a scientific and medical practice. Through his careful observation, experimentation, and precise terminology, Braid laid the groundwork for the clinical use of hypnosis that continues into the present day.

Braid was born near Manchester but trained and practised as a surgeon primarily in Scotland and England. In the 1830s and 1840s, mesmerism – named after Franz Anton Mesmer – had gained widespread attention. Mesmer proposed the existence of a mysterious “animal magnetism” that could be manipulated by practitioners to heal illnesses and induce trances. Demonstrations of mesmerism often had a theatrical quality, and while some believed fervently in its powers, many in the medical community remained sceptical. Braid himself first encountered mesmerism in 1841 when he attended a public demonstration and noticed that the effects on the subjects seemed genuine but did not require any invisible magnetic fluid to explain.

Intrigued by what he saw, Braid began experimenting with inducing similar trances using simple techniques of focused attention. He discovered that by asking a subject to fixate on a bright object, such as the top of a bottle or a candle flame, and maintain a steady gaze while relaxing, a state of profound mental concentration and altered awareness could be achieved. He concluded that the phenomena attributed to mesmerism were, in fact, the result of physiological and psychological processes rather than magnetic forces.

Braid coined the term “hypnotism” in 1843, deriving it from the Greek word “hypnos” meaning sleep, because the trance state bore some superficial resemblance to sleep. He quickly realised that the state was not true sleep but a condition of heightened suggestibility and focused attention. He later attempted to replace the term with “monoideism” to better describe the narrowing of the mind to a single dominant idea or focus, but “hypnotism” remained the popular expression.

Braid’s approach was methodical and aimed to bring respectability to the practice. He demonstrated that hypnosis could be induced without any mystical rituals and that its effects could be explained by natural laws. He showed that hypnosis could reduce pain and produce anaesthesia, which was particularly significant in an era before the widespread use of chemical anaesthetics. Braid performed minor surgical procedures under hypnotic trance and reported successful results, adding to the credibility of his method.

In addition to its potential for pain relief, Braid explored the therapeutic applications of hypnotism for functional nervous disorders, such as headaches, anxiety, and certain psychosomatic conditions. He emphasised that the effects of hypnotism were largely dependent on the subject’s state of concentration and willingness, rather than the operator possessing any special power.

Braid published his findings in works such as “Neurypnology” (1843), in which he outlined his theories and methods of induction. He stressed that hypnotism was fundamentally a psychological phenomenon, rejecting the superstition and spectacle that had characterised mesmerism. His scientific framing of hypnotism helped to shift it from the fringes of entertainment into the realm of legitimate medical inquiry.

Although Braid died in 1860, his ideas continued to influence physicians, psychologists, and researchers in the decades that followed. The late nineteenth century saw the growth of interest in hypnotism in France, particularly through the work of Jean-Martin Charcot and the Nancy School, which further developed the scientific study of suggestion and the subconscious. Modern hypnotherapy and the clinical use of hypnosis for pain management, stress reduction, and behavioural change can all trace their intellectual roots to Braid’s pioneering insights.