I have long been fascinated by codes and cyphers, as readers of my Sir Anthony Standen Adventures will be aware. So today’s post is about Enigma.

On the 30th of October, 1942, Lieutenant Francis Anthony Blair Fasson was drowned together with Able Seaman Colin Grazier whilst they recovered code books from the sinking German submarine, U-559. They were both awarded the George Cross for outstanding bravery and steadfast devotion to duty in the face of danger. NAAFI canteen assistant Tommy Brown, who had boarded the submarine with them, survived and managed to get the codebook back to HMS Petard. He was awarded the George Medal. The recovery of a German codebook was exactly the breakthough required to help the code-breakers at Bletchley Park crack Germany’s “unbreakable” Enigma machine.

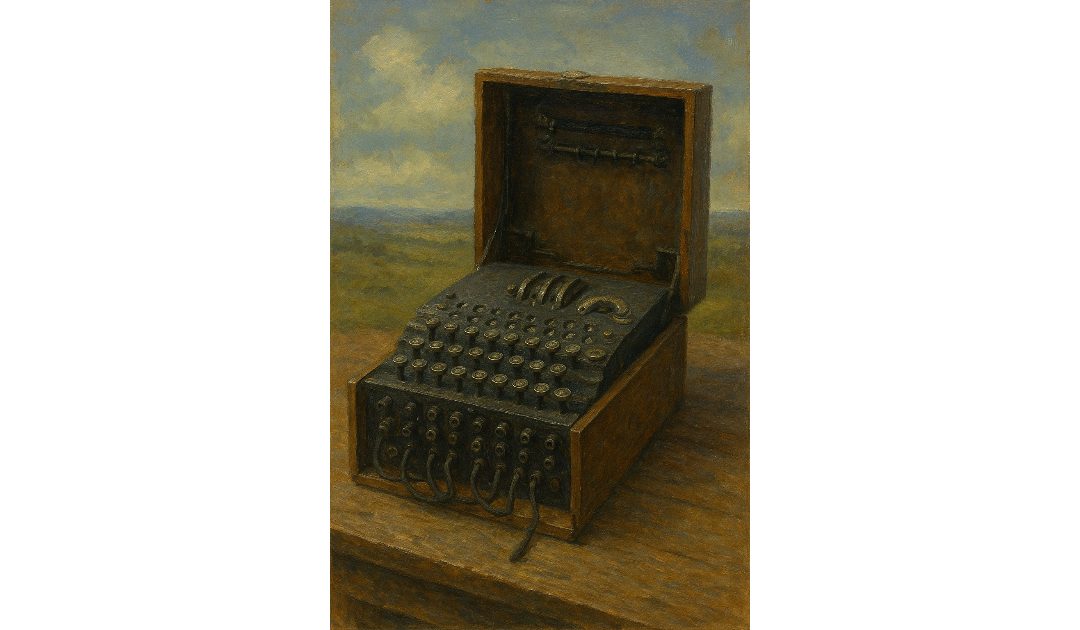

Invented by German engineer Arthur Scherbius in 1918, the Enigma machine resembled a typewriter with an array of rotors and electrical circuits. Messages typed on the machine would be encrypted into seemingly random letters, which could then be transmitted securely via radio. To decrypt the message, the recipient needed an Enigma machine set to the exact initial configuration as the sender’s.

The core of Enigmas security lay in its rotors, which rotated with each keystroke, changing the electrical pathways and thus encrypting each letter differently. The machine also featured a plugboard (Steckerbrett) that further scrambled the letters, significantly increasing the number of possible encryption combinations. The combination of rotors, their order, starting positions, and plugboard settings created an astronomical number of potential configurations, estimated to be around 150 quintillion.

Despite its complexity, Enigma was not unbreakable. The first significant breakthroughs came from Polish mathematicians Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różcycki, and Henryk Zygalski in the early 1930s. Using mathematical analysis and information obtained from a German traitor, they managed to replicate an Enigma machine and developed techniques to deduce daily key settings. Their pioneering work laid the foundation for future codebreaking efforts.

As tensions escalated towards World War II, the Polish shared their findings with British and French intelligence in 1939. This collaboration sparked a concentrated effort at Bletchley Park, the British codebreaking centre, where brilliant minds such as Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman took up the challenge. Alan Turing, a mathematician and logician, designed the Bombe, an electromechanical device to automate the process of finding Enigmas settings. The Bombe could test thousands of possible settings rapidly, narrowing down the correct configuration through a process of elimination based on known plaintext characteristics, known as ‘cribs.’

One crucial breakthrough was exploiting the Germans’ operational habits and procedural errors. For instance, German operators often reused phrases or had predictable message structures. These consistencies provided entry points for codebreakers to hypothesise parts of the plaintext and match them against the encrypted messages.

Historians estimate that the work at Bletchley Park shortened the war by at least two years and saved millions of lives, as did the bravery of Tony Fasson,

Colin Grazier, and Tommy Brown.