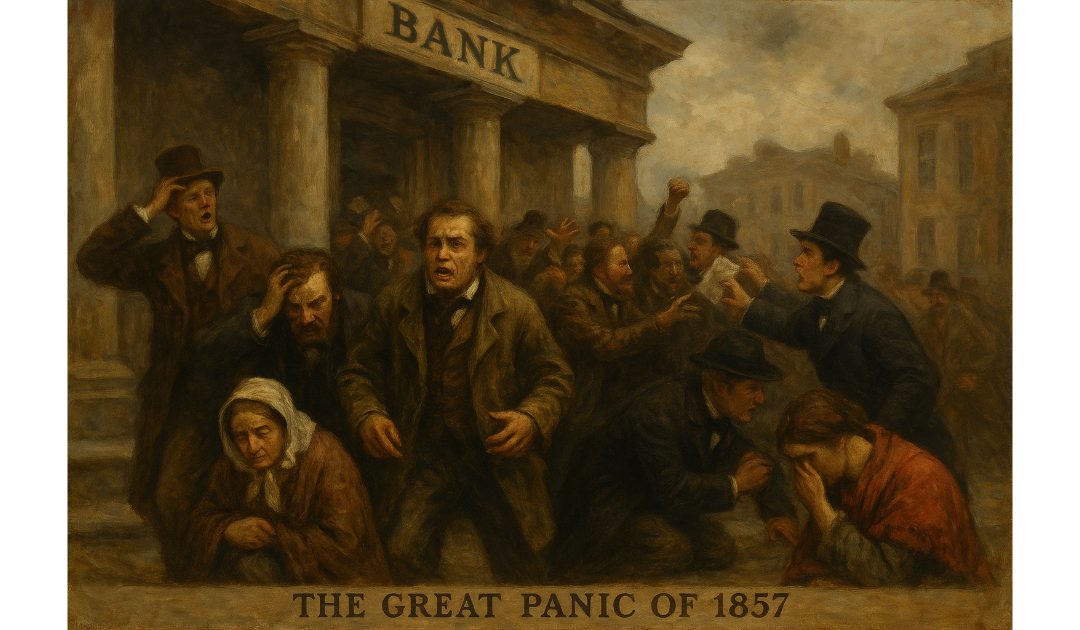

I have recently given a friend of mine some investment advice. He has had a very poor record of investment in the past, so much so that he thought his investment had, in some mysterious way, brought about the collapse of the companies he had invested in. Of course this was not so, he simply had not thought his investments through enough. I hope my advice helps, because he has been, in part, inspiration for aspects of the Sir Anthony Standen Adventures. Anyway, I find I have already covered many of the events of the 24th of August, but not the Great Panic of 1857.

The Great Panic of 1857 was a significant financial crisis that reverberated through the global economy, with its epicentre in the United States and widespread effects felt in Europe and beyond. It marked one of the first worldwide economic crises, underscoring the interconnectedness of expanding international markets and the vulnerabilities inherent in emerging financial systems.

Background and Causes

The mid-19th century was a period of robust economic growth, driven by industrial expansion, railroads, and burgeoning international trade. The United States, in particular, experienced rapid westward expansion, supported by land speculation and a booming railroad industry. However, this growth was fuelled by speculative investments, easy credit, and an overreliance on unstable banking practices.

One of the central causes of the Panic was the collapse of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company in August 1857. This prominent financial institution had significant investments in railroads and real estate. Its failure, due to fraudulent activities and risky lending, triggered widespread fear, leading to a loss of confidence in the banking system. Investors rushed to withdraw their funds, creating a ripple effect across the financial sector.

Compounding this was the declining international demand for American agricultural products, particularly wheat. Poor harvests in Europe in previous years had bolstered American exports, but once European agriculture recovered, demand plummeted. This decline severely affected American farmers and land speculators who had relied heavily on export markets.

The Financial Collapse

The panic spread rapidly through the financial networks. Banks, already weakened by speculative lending, began to fail. The interconnectedness of institutions meant that the collapse of one could trigger a chain reaction. The New York money market, a critical hub of financial activity, experienced severe distress as confidence eroded.

Railroads, seen as the backbone of the American economy, were among the hardest hit. Many had been financed through speculative investments and loans that could no longer be serviced. As railroad companies defaulted, associated industries, including ironworks and construction, faced massive layoffs and bankruptcies.

Public panic ensued, with widespread bank runs where depositors demanded their money in cash, fearing insolvency. In response, banks across the United States suspended specie payments, meaning they no longer redeemed banknotes for gold or silver. This suspension further undermined trust in the financial system.

International Repercussions

The Panic of 1857 was not confined to the United States. Its effects rippled across the Atlantic, impacting European markets. Britain, heavily invested in American railroads and reliant on transatlantic trade, experienced financial distress. Banks in London faced liquidity crises, and the British economy contracted.

Germany also felt the impact, particularly in regions engaged in heavy industry and export-oriented businesses. The crisis highlighted the vulnerabilities in the global credit system and the risks of overextension in international finance.

Government Response and Aftermath

In the United States, the federal government’s response was limited, reflecting the laissez-faire economic philosophy of the time. President James Buchanan downplayed the severity of the crisis, attributing it to over-speculation rather than systemic issues. Unlike future financial crises, there was no central bank to coordinate a comprehensive response.

However, some measures were taken. The Tariff of 1857, which had reduced duties and contributed to fiscal deficits, was partially reversed to stabilise federal revenues. Additionally, some state governments attempted to support failing banks, but these efforts were often insufficient.

The crisis led to widespread unemployment, business failures, and a significant contraction in economic activity. It particularly devastated the northern industrial states, while the agrarian South was relatively insulated, exacerbating sectional tensions that would later contribute to the American Civil War.

Long-term Impacts

The Panic of 1857 had far-reaching consequences. It exposed the fragility of the banking system and the dangers of speculative investment without adequate regulatory oversight. The crisis prompted calls for banking reform, leading to the eventual establishment of a more centralised banking system in the United States with the National Banking Acts of the 1860s.

It also influenced political debates. The economic distress weakened the Democratic Party, which had championed laissez-faire policies, and strengthened the emerging Republican Party, which advocated for protective tariffs and infrastructure development to stabilise the economy.

In a global context, the Panic of 1857 underscored the growing interdependence of international financial markets. It served as an early lesson in the potential for localised financial issues to escalate into worldwide economic crises—a phenomenon that would become all too familiar in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Conclusion

The Great Panic of 1857 serves as a critical historical example of the complexities and vulnerabilities of financial systems during periods of rapid economic expansion. Its causes—speculative investment, inadequate regulatory frameworks, and overreliance on unstable credit—remain relevant to modern economic discussions. The crisis not only reshaped the American economy but also provided enduring lessons on the importance of financial stability and the need for responsive economic policy in times of distress.