The 9th of June is most famous for being my wedding anniversary, but amongst the other events on this date is the suicide of Emperor Nero, one of history’s most notorious and intriguing figures. Emperor Nero, whose reign from 54 to 68 AD is often remembered for its tyranny, extravagance, and the devastating Great Fire of Rome. Yet, Nero’s legacy is a complex tapestry woven from historical accounts, myths, and biases. This blog post delves into the enigmatic life and rule of Emperor Nero, exploring his rise to power, key events during his reign, and the lasting impact of his leadership.

Nero was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in 37 AD, the son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Agrippina the Younger, who was the sister of Emperor Caligula and niece of Emperor Claudius. After the death of Caligula, her fortunes improved when Claudius became Emperor. Agrippina married her uncle, Claudius, in 49 AD, and used her influence at court to promote her son, Nero, over Claudius’s own biological son, Britannicus.

In 54 AD, Claudius died under suspicious circumstances, possibly poisoned by Agrippina, and Nero ascended to the throne at the tender age of 16, becoming Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus. Initially, Agrippina’s influence was significant, governing through her son, but as Nero matured, he began to resent her control.

Nero’s early years as emperor were marked by promising reforms and wise counsel. His advisors, including the philosopher Seneca and the Praetorian Prefect Burrus, helped him govern effectively. During this period, Nero abolished capital punishment, reduced taxes, and allowed more independence for the Senate. These early successes painted him as a capable leader, earning him public favour.

However, the harmony was short-lived. Nero’s relationship with his mother deteriorated, ultimately leading to her murder in 59 AD. This matricide marked a turning point in Nero’s reign, as he increasingly indulged in artistic pursuits, extravagant spending, and self-indulgence.

One of the most infamous events during Nero’s reign was the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. The fire raged for six days, devastating much of the city. Rumours circulated that Nero himself had started the fire to clear land for a new palace, the Domus Aurea, although there is no conclusive evidence to support this claim.

In the aftermath, Nero undertook massive reconstruction efforts, implementing new building codes to prevent future disasters. Yet, he needed a scapegoat to deflect the blame. He targeted Christians, a fledgling religious group, subjecting them to brutal persecution that would stain his legacy.

Nero fancied himself an artist, passionately pursuing music, theatre, and chariot racing. He participated in competitions across Greece, often rigged in his favour, which led to widespread mockery back in Rome. His artistic pursuits alienated the Senate and aristocracy, who viewed them as unbecoming of an emperor.

Despite his unpopularity among the elite, Nero’s lavish games and public spectacles endeared him to the common people. His eccentricities and refusal to conform to traditional Roman expectations became hallmarks of his reign.

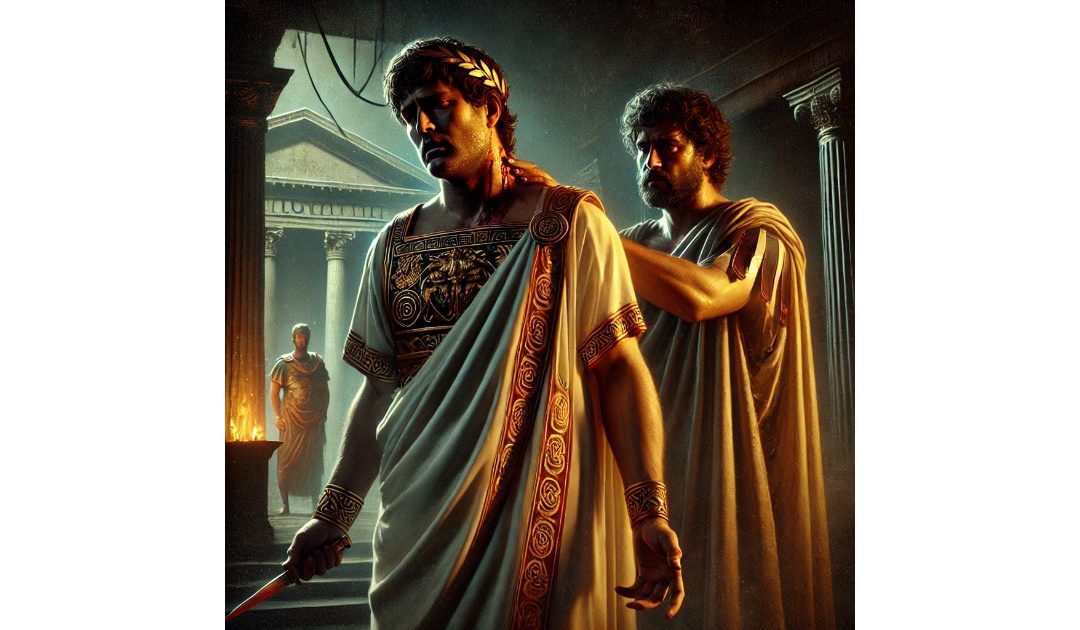

By 68 AD, Nero’s reign was plagued by multiple revolts and conspiracies. Financial mismanagement, political assassinations, and military defeats eroded his support base. The revolt led by Gaius Julius Vindex in Gaul marked the beginning of the end. As opposition grew, the Senate declared him a public enemy, and his own guards deserted him.

Facing imminent capture, Nero fled Rome. On 9th June 68 AD, he took his own life, famously uttering “What an artist dies in me!” His death marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, plunging Rome into a year of civil strife known as the Year of the Four Emperors.

Nero’s reign remains one of the most contentious periods in Roman history. Early historians like Tacitus and Suetonius painted him as a tyrant and madman, a narrative perpetuated through centuries. However, modern historians have begun to reassess his rule, suggesting that much of his vilification might stem from political bias and sensationalism.