I recently posted about the Roman Emperor Commodus, but today belongs to the most famous Roman Emperor, Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon River on the 10th of January 49 BCE is one of the most significant events in Roman history, marking a pivotal moment that led to the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of imperial rule. The phrase “crossing the Rubicon” has since become synonymous with making an irreversible decision, often with significant consequences.

The Rubicon River, a small waterway in northern Italy, served as a boundary between the province of Gaul, which was under Caesar’s command, and Italy, which was under the control of the Senate. According to Roman law, a general was forbidden from bringing his army into Italy, as this was seen as an act of treason. Caesar had spent nearly a decade in Gaul, where he had achieved remarkable military successes, expanding Roman territory and gaining immense popularity among his troops and the Roman populace.

However, his growing power and influence alarmed many in the Senate, particularly those who viewed him as a threat to the Republic. Political tensions escalated as Caesar’s rivals, including Pompey the Great and other senators, sought to curtail his power. In 50 BCE, the Senate, influenced by Pompey and his supporters, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome as a private citizen. This demand was unacceptable to Caesar, who feared that without the protection of his loyal soldiers, he would be vulnerable to political attacks and possibly face prosecution.

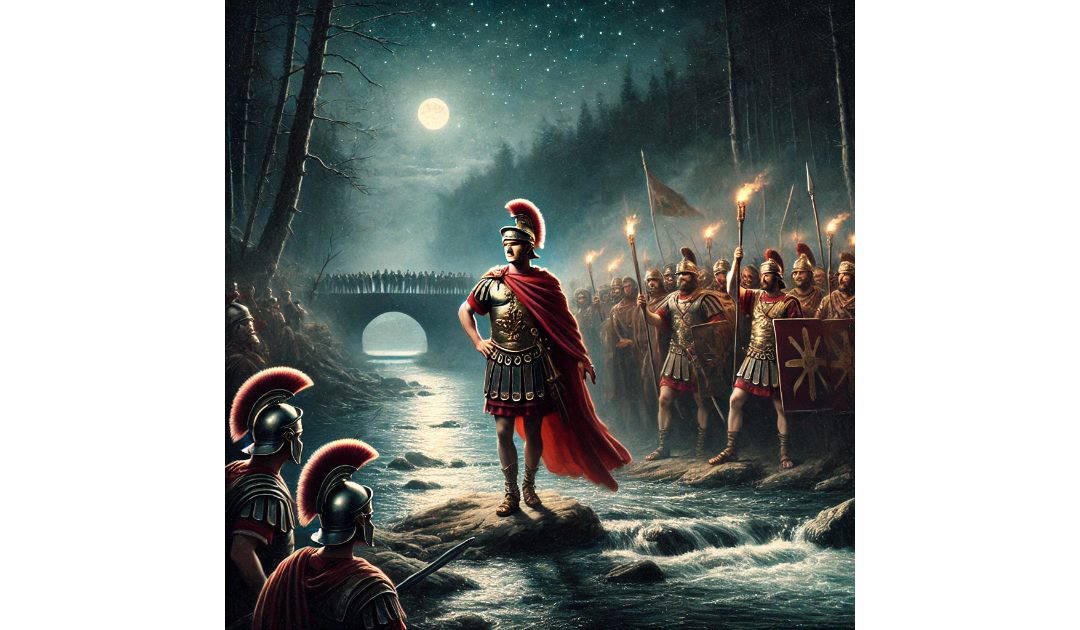

Faced with a critical decision, Caesar deliberated on his next steps. He understood that crossing the Rubicon would be tantamount to declaring war against the Senate and Pompey. Yet, he also realized that retreating would mean abandoning his power and achievements in Gaul. On 10th January 49 BCE, Caesar made the fateful decision to cross the Rubicon with his army. According to historical accounts, as he approached the river, he famously uttered the phrase “Alea iacta est,” which translates to “The die is cast.” This declaration signified his commitment to the course of action he had chosen, acknowledging that there was no turning back.

The crossing of the Rubicon ignited a civil war in Rome. Caesar’s forces swiftly advanced toward Rome, and Pompey, recognizing the threat, fled the city with his supporters. The Senate, now in disarray, declared Caesar a public enemy, but he continued to gain support from the populace and his loyal legions. His military acumen and charismatic leadership allowed him to secure several victories against Pompey’s forces, ultimately leading to Pompey’s defeat and death in 48 BCE.

The consequences of Caesar’s actions were profound. His decision to cross the Rubicon not only altered the political landscape of Rome but also set in motion events that would lead to the end of the Republic. In 44 BCE, Caesar was appointed dictator for life, a title that further alienated him from the traditional Republican values of shared power and governance. His concentration of power and reforms aimed at addressing social issues and the needs of the populace garnered both admiration and resentment.

Ultimately, Caesar’s rule ended tragically when he was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 BCE by a group of senators who feared his growing power and the potential establishment of a monarchy. His death sparked another wave of civil wars, leading to the rise of his adopted heir, Octavian (later Augustus), and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

In summary, Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon was a defining moment that not only changed the course of his life but also transformed the Roman political landscape forever. It symbolizes the tension between ambition and legality, the struggle for power, and the consequences of decisive action in the face of uncertainty. The phrase “crossing the Rubicon” continues to resonate today, reminding us of the weight of our choices and the paths they set us on.