I went with my father when he visited the Rifle Brigade Museum in Winchester, when I was a boy. He was looking for a book, The Rifle Brigade Chronicle, but he didn’t know which edition. He knew that it had his name in it, and that it was in an article written by Lieutenant.-Colonel Vic Turner V.C. The curator was very helpful, and I have it in front of me now. It’s the 1955 edition and contains the article “AN INDIAN DUCK SHOOT OR A FIRST INTRODUCTION TO WAR”. It spans seventeen pages, so I shall have to précis it ruthlessly.

It starts with General Messervy telling Turner that he had “no experience of desert warfare and that he was now going to do some training with a real live enemy. I don’t think you will have any serious fighting, as intelligence reports that not more than forty-eight combined Axis tanks have got back across the Wadi Faregh.” He went on to add, “In fact, gentlemen, it will be exactly like an Indian duck shoot!” As Turner says in his account, “And so it was except that we were the poor ruddy duck.”

Not long into duck shoot, Turner’s column of vehicles endured several attacks by Stuka dive-bombers. Running into a group of Italian tanks reduced the numbers in his column further. When they met up with another allied column, they learnt that the Germans had broken through and were advancing rapidly. Turner now had a column of twenty-three vehicles. They ploughed their way across the desert, through one wadi (valley) after another, until in one wadi they encountered an Italian tank formation on one side and a German tank formation on the other. They made a dash for it, under intense fire. When clear, they had nine vehicles left. They abandoned the most badly damaged, and the armoured car as it used too much petrol. Further on they encountered what they thought was a South African troop, until they began attacking them. He had now lost all his vehicles. He led the remaining eleven men on foot. Walking by night and laying up during the day. They managed about fifteen miles per day through the desert.

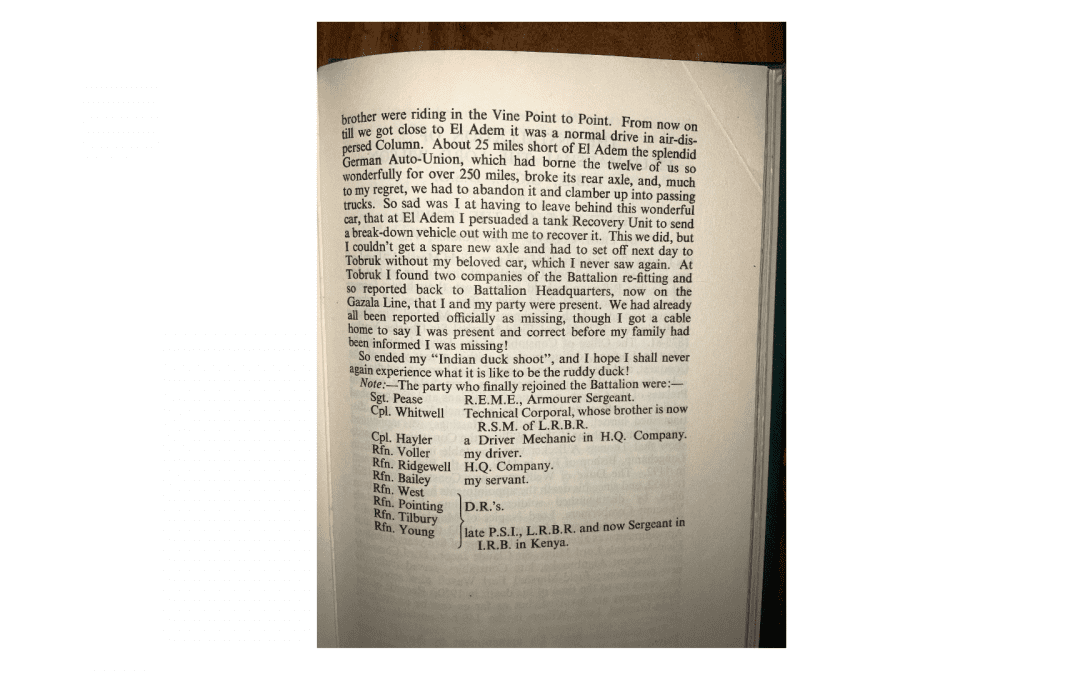

When they came across a road, he decided they’d try and capture a vehicle. They drew lots, and when they heard a German staff car approaching, Corporal Hayler staggered out looking exhausted. The car stopped and was captured. The Germans were disarmed, but the car, an Auto Union would not carry twelve plus prisoners. Turner didn’t want the prisoners to quickly raise the alarm, so decided to immobilise them by cutting off their trouser buttons. Apparently the sight of an enemy approaching your trousers wielding a bayonet is quite terrifying. Turner eventually rejoined our forces at Tobruk, with ten men, one of whom was my father. The account doesn’t explain how twelve became eleven. They had all been posted as missing in action.

Turner was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in the battle of El Alamein. My father next met him just before D-Day. Dad was a dispatch rider, re-united with his trusty motorcycle. He was delivering a dispatch and passing a table where Montgomery, Eisenhower and other allied top brass were in conference. Vic Turner was amongst them and shouted “West”. He left the conference and wanted to know how my father was getting on. After the salute, Turner wanted to shake my father’s hand. “It’s a bit greasy I’m afraid, sir.” “Never mind that, West.” Turner said grasping my father’s hand and shaking it. That was the sort of man Vic Turner was. No wonder he was made Lieutenant of the Queen’s Bodyguard in 1967. They deserved each other, exceptional people. And my dad found a book with his name in it. There’s something about a book with your name in it, or on it.